Sylvana Gavilanes was 13 when Chicago Public Schools closed down Trumbull Elementary, which sat on a busy corner in Andersonville on Chicago’s North Side. Of the 400 students at Trumbull, more than half were Latino, a third were bilingual, and a third received special education services. Sylvana fit into all three demographics.

Her mother, Maria, had prayed CPS would spare Trumbull, one of the few schools considered for closure that wasn’t majority black or on the South or West sides. But neither prayers, nor lawsuits, could save it. In May 2013, the board of education voted to close 50 Chicago schools, including Trumbull. And Maria began the stressful process of finding another school for her daughter, an avid reader with a computer memory—but who says few words.

Diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at age 5, Sylvana struggled with new people and new places. Routine was crucial. Her parents ultimately settled on McPherson Elementary in nearby Ravenswood. After her first day at McPherson, Sylvana returned to her family’s Albany Park apartment, had a snack, and rushed to watch a DVD that her teachers at Trumbull had made her. It played nice, soft music, and showed pictures of various music recitals and school plays she had participated in with her classmates.

When the DVD was over, Sylvana headed to a corner in her living room, turned her back on her mother, and began to cry. She did the same thing every day after school for nearly two months.

“She was missing her friends there, the teachers. It was a difficult adjustment for her at the new school,” Maria said. “It was heartbreaking to see her cry.”

Transferring to a new school can be hard on children. For Sylvana, a typically cheerful teen who loves blues music, especially B.B. King, the change was particularly challenging. But the Gavilanes family wasn’t the only one having a hard time. Of the nearly 11,000 K-7 students who had to switch schools because of the closings, almost 2,000—practically one in five—received special education services.

Like many of their parents, Maria feared the transition would disrupt the emotional bonds and academic progress made by her child. “I’m very concerned it will affect her development, in all areas—academically and socially,” she said then.

As we know now, the next five years would mean a lot of cost-cutting, which led to big changes for Chicago’s public schools—and for its special education students. This spring, the state took over CPS’ special education program, an action spurred by an investigation that found a 2016 overhaul led to delayed or denied services for scores of students with special needs. Five years now marks the end of a moratorium on school closings: This fall, the district will again start closing schools. And, while fewer students are being displaced overall, the proportion of special education students is even higher than before—one in three. CPS, meanwhile, appears to have no clear road map on how to transition these students to new schools.

Meanwhile, this question lingers: What happens to students in special education when Chicago closes schools?

And what happened to Sylvana?

Chicago has the unfortunate distinction of overseeing the biggest mass school closing in U.S. history. We’re still unpacking the meaning and impact of what happened.

The school closings were a matter of math, according to the schools chief at the time, Barbara Byrd-Bennett, and Chicago’s mayor, Rahm Emanuel. The district warned of a $1 billion budget deficit, and of a “utilization crisis” in the city, which African-American families had been leaving in droves. There were 403,000 students enrolled in CPS schools—but the district said it had capacity for 511,000. Pressure was being applied from the outside, too: There were federal calls to close low-performing institutions.

In May, the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research released a study saying that the closings induced a period of “mourning,” freighting teachers and students alike with enormous stress and hurting students’ performance, particularly in math. Students and staff appreciated the new technology, resources, programs and other investments they encountered at 48 “welcoming schools”; however, those investments weren’t sustained, and the consequences of the closings still loom over the district today.

But while the consortium report examined the experiences of educators and families in the chaotic months leading up to the closings and how students performed academically in the years after, it doesn’t say much about the particular impact on special education students. And while the state’s investigation acknowledges policies that hurt special education, it only explored the years after the closings. The final recommendation from the Illinois State Board of Education doesn’t address the closings at all.

For many parents, there’s never a good time to change schools for a student who has a disability. One decision can have lasting impact and can threaten progress, especially for students who are developmentally delayed or have a shortened development window.

When Trumbull closed in late May 2013, Maria scrambled to prepare her daughter, who was born with dislocated hips and struggled as a toddler to walk and speak. The timing couldn’t have been worse: Sylvana was entering eighth grade—that crucial year before high school.

Sylvana had been a student at Trumbull since fourth grade, and she had made considerable progress, her mother said. In her time there, Maria saw improvements to her daughter’s motor skills, her ability to focus and communicate, and her comfort level in social situations. Maria had never thought her daughter would do some of the things she accomplished: opening doors, flipping light switches, typing, solving fractions. She attributed the improvements to Sylvana’s time at Trumbull.

“[Teachers] were very well trained to deal with autistic kids, and she got occupational, physical and bilingual speech therapy. I could see her progressing. She always liked reading, but she would be more involved in her books.”

"It was heartbreaking to see her cry."

Maria Gavilanes

Her mother was especially appreciative that Sylvana’s teacher, Michele Van Pelt, had given the family tips on how to support learning at home. To teach Sylvana math, Van Pelt showed Maria how to practice using coins rather than flash cards: Autistic children sometimes struggle with abstract thought, and coins are a more concrete representation of numbers. Sylvana began to write legibly, too, after her teacher suggested she practice writing with a big pencil or crayon for an easier grip.

When Sylvana moved to Trumbull after third grade, she had arrived at her new school armed with a booklet that pictured the outside and inside of the building. She had toured the school and met with her future teacher over the summer. Later, when she moved up grades and changed teachers, the staff would invest time in preparing for her transition, gathering and exchanging information. One teacher would prepare a booklet with the new teacher’s room number, name and picture for Sylvana to keep throughout the summer.

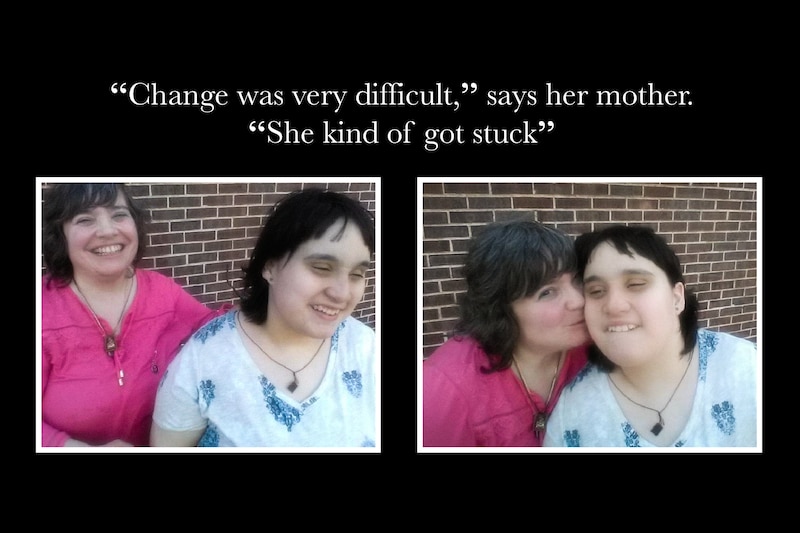

“It was good for her because change was very difficult,” Maria said.

Sylvana lived in Albany Park with Maria, a counselor in a women’s social services center, and her father, Jerry, a Chicago Transit Authority bus driver. When Maria sought a new school for her daughter, she chose McPherson. The 650-student school was nearby, and it had good reviews. About 16 percent of its students had Individualized Education Plans, or IEPs, which meant they received some type of special education services.

By the next school year, McPherson had 130 more students. The percentage receiving special education services had increased, too, to 20.5 percent.

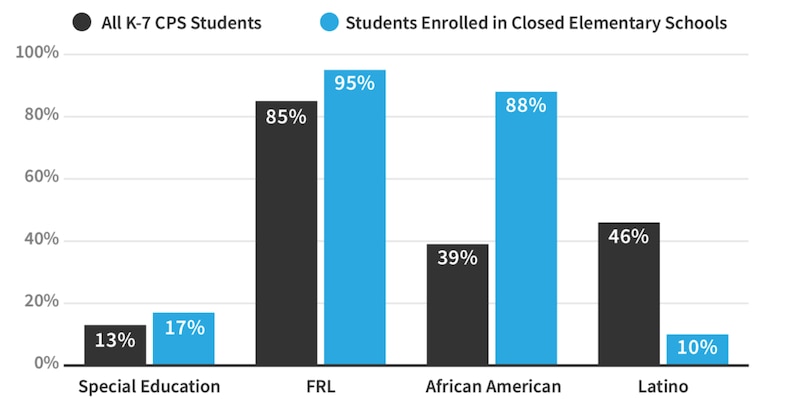

In CPS at large in 2013, about 13 percent of students were enrolled in special education programs. Researchers are still trying to understand why, taken all together, the schools that closed had a proportion closer to 17 percent.

Currently, there’s a study underway at the University of Illinois at Chicago to see if the percentage of IEPs at a school predicts the likelihood of that institution being closed. Federico Waitoller, the UIC professor behind the study, trains special education teachers. He suspects that the space utilization formula used to determine which schools were underenrolled and eligible for closure in 2013 didn’t account for dramatically smaller class sizes for some special education programs. Students in cluster programs ideally require smaller class sizes—and in 2013, one in three schools that closed had cluster programs.

In other words: “The hypothesis is, the larger your percentage of students with disabilities, you’ll be more likely to have a lower utilization,” Waitoller said.

Waitoller has studied the effects of CPS school closings, and he doesn’t believe there’s a good, comprehensive study that examines the impact of school closings on students with disabilities. Without that, it’s hard to believe the district has research that it could use to inform future closings, he said.

“It’s very difficult to say we’re going to learn a lesson when we don’t know what the lessons are,” he added.

Kate Gladson, a staff attorney at LAF, formerly known as the Legal Assistance Foundation, can list some takeaways from her own experiences. From 2014 to 2016, Gladson represented about 50 students in cases involving special education and school discipline as part of a two-year Equal Justice Works Fellowship. Most of the schools involved her cases were affected by the closings, including several designated “welcoming schools.”

“School closings in 2013 were disruptive for all kids at closing and welcoming schools, but students with special education services have a different set of challenges,” Gladson said.

Parents wanted their children to have the supports they needed to learn and progress, and they wanted placements in schools close to home. But, as a 2015 University of Chicago consortium report noted, parents received limited information from the district.

“In some cases, families realized that the supports at the designated welcoming school were not adequate and had to look for other schools in the district to meet their children’s needs,” the report said. It recommended providing parents with more information and time to make informed decisions.

"It’s very difficult to say we’re going to learn a lesson when we don't know what the lessons are."

UIC researcher Federico Waitoller

Once children were enrolled at schools, other problems arose. The district re-evaluates IEPs every three years, and the closings turned the evaluation process on its head for students who required initial evaluations or for whom re-evaluations were due, Gladson observed. Teachers at welcoming and receiving schools were getting to know their new students, and records and data from previous schools were not always available, she said.

Even when the IEPs were completed, children from closed schools who transitioned to welcoming schools were sometimes left without the resources to support their plans, Gladson said. The impact was felt, too, on students in the welcoming schools. “There was a disruption to their educational experiences as well.”

None of Sylvana’s teachers followed her to McPherson in 2013. The school was being remodeled, so Sylvana wasn’t able to attend summer school, and she didn’t meet her McPherson teacher until the first day of classes. The school did have a lot to offer: Maria liked the principal and school counselor, and, unlike a lot of CPS schools, McPherson had a librarian.

But Maria said that Sylvana had a rough time in the classroom at McPherson. “She wasn’t responding as much at McPherson as I saw her responding at Trumbull. I feel she kind of got stuck. She wasn’t as motivated,” Maria said.

Sylvana’s grades dropped. She had been receiving speech and sensory therapy but now those things weren’t offered. Maria said the kids in class were more functional than her daughter; many had been at the school for years.

Maria conceded that Sylvana and other students from closed schools must have presented a challenge for the staff at McPherson. An administrator at McPherson did not return calls seeking comment.

Back in 2013, CPS CEO Byrd-Bennett knew the closings would be hard. But as she said in a statement then: “I also know that, in the end, this will benefit our children.”

By mid-2015, her tenure was over, wrecked by a corruption scandal. Her successor was Mayor Emanuel’s chief of staff, Forrest Claypool, who had deep ties to the Democratic Party and a scant education resume. Under Claypool, CPS made drastic changes that created systematic obstacles and delays in special education—changes that, after a WBEZ report, the Illinois State Board of Education concluded violated the federal Individuals with Disabilities Act.

Claypool eventually stepped down in 2017 amid ethics violations, and in January 2018 was replaced by Janice Jackson, a former principal who had been serving as chief education officer. A month later, the Chicago Board of Education voted to open a new $85 million high school in Englewood and close or phase out four “underutilized” high schools.

Robeson High School will close this summer, while Harper High, Hope High, and Team Englewood will be phased out over three years. The schools have a combined enrollment of 392, and 129 of those students are in special education.

Earlier this year, CPS announced new guidelines for the formula it uses to determine a building’s utilization, saying it would acknowledge “unique space challenges and the need for greater program flexibility” at schools and account for special education cluster programs. When Chalkbeat asked officials at CPS for other policy changes that might minimize the impact of school closings on students in special education, none agreed to an interview on the record. Instead, a spokeswoman sent an email that stressed that the district has learned that “sustained, individualized supports can facilitate better outcomes” for all students and that the lesson “is being implemented” in Englewood:

The email said students will receive the following:

- Up to $1.5 million for academic and social/emotional supports, like after-school programs and dedicated social workers.

- An unspecified amount of budgetary support for under-enrolled schools.

- Detailed, individualized transition plans that include safety and transportation.

- Summer jobs, tutoring, and other chances to engage with their new school communities before the school year begins.

But nothing in the CPS response was specific to special education, and the district declined to provide further information.

Chris Yun, an education policy analyst with Access Living, a disability rights advocacy group, said there’s a lot CPS can learn from the school closings when it comes to special education students. One is having somebody on the school board who is specialized in the topic so that decisions are informed by specific expertise. Another is a mechanism that ensures students displaced by closings get special education services at their new schools without interruption, as required by law, regardless of cost or red tape.

Federico Waitoller of UIC says a school closing is inherently disruptive. But if it has to happen, there should be several steps to mitigate emotional and academic harm students might suffer.

“How do you give a sense of belonging and trust?” Waitoller asked. “That’s a huge challenge, and that’s more than a technical question.”

Asked how educators can create a sense of belonging, he said it takes time. “It happens through relationship-building activities, focusing on the human aspects of learning.”

Among his other suggestions: bringing over as many special education teachers from the closing school to the new one to foster a smooth transition and managing teacher stress. It’s crucial, too, that teachers at the new schools have the training and skills to meet students’ needs and that the district sustain its investments beyond the first year of impact.

"I personally thought we could do it on our own. But I have to listen to the will of the people."

CPS CEO Janice Jackson

In late May, not long after the consortium report on school closings was released, CPS’ Jackson stood at a public forum at Michele Clark High School in Austin and fielded questions from a parade of parents and advocates. Toward the end, a grandparent asked: “What can we do as a whole to make special education better?”

Jackson started by acknowledging CPS has a long way to go and touted efforts to add special education funding, positions, and services.

“I personally thought we could do it on our own,” Jackson said. “But I have to listen to the will of the people.”

Even this spring, Maria Gavilanes hadn’t heard that the district’s special education population was at the center of a state investigation or that an independent monitor was taking over the program. She said the problems reminded her of her own experiences, and how her daughter stopped receiving speech therapy at McPherson.

Life hasn’t been easy for Sylvana since she graduated from eighth grade. She lost her father, Jerry, to a heart attack in 2015, and weathered a long period of mourning. But Maria said Sylvana is recently back to her cheerful self, and when it comes to school, things are better.

Despite Sylvana’s struggles at McPherson, there were bright spots: The counselor there helped her mother navigate the application process and gain entry into North Side Learning Center, a district-run school for about 220 students with intellectual disabilities. Beyond academics, students there practice skills that prepare them to live independently and work in the community. Sylvana, 18, can take classes there for two more years before she graduates. Her mother’s hope is for her to one day have a job, maybe clerical work in an office or factory doing something like packaging.

Maria knew that Sylvana would face certain challenges in life. School closings were just one. But she can’t help but wonder if losing Trumbull slowed down her daughter’s momentum and affected the trajectory of her progress. Still, she’s grateful her ordeal lasted just one year. Plenty of families are still searching for a better situation.