While few communities would say their public school is adequately funded, in Chicago a gap yawns between have and have-not campuses, separating schools where parents can raise funds to supplement staff and supplies, and those where teachers struggle to meet students’ complicated needs.

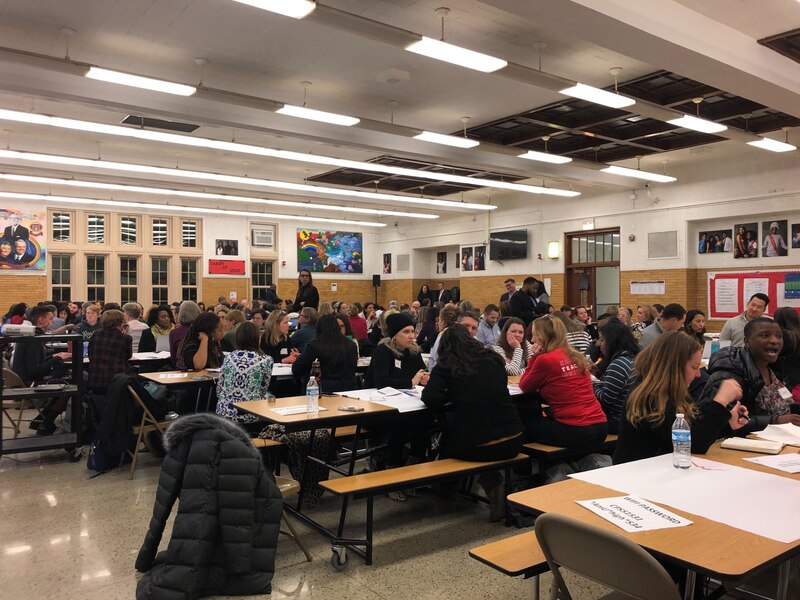

Mayor Lori Lightfoot pledged to revamp how the district doles out funds. On Wednesday, the first public meeting called by a committee overseeing the overhaul attracted about 140 people brimming with ideas and questions on how to redo school budgeting.

But even as participants agreed on the need for change, few had ideas on how to address the elephant in the room — how to fix school funding without more money?

Spurred by the possibility that the district might at long last heed the public’s complaints about insufficient funding, parents and teachers shared ideas on how to better serve students’ needs and spread out opportunity.

Chicago differentiates somewhat in how much it allocates schools serving middle-class students and those serving needier ones. Campuses get more funds for students living in poverty and those requiring special education. But educators and parents have said that’s not enough, and that schools serving students who face learning challenges, language barriers, and other difficulties need more resources.

As a candidate, Lightfoot promised to revisit school funding and to consult the public about it, and last month the city created a working group to lead the charge.

Wednesday’s meeting was the first of six to be held in the next two weeks. School board members Sendhil Revuluri and Elizabeth Todd-Breland also attended the gathering.

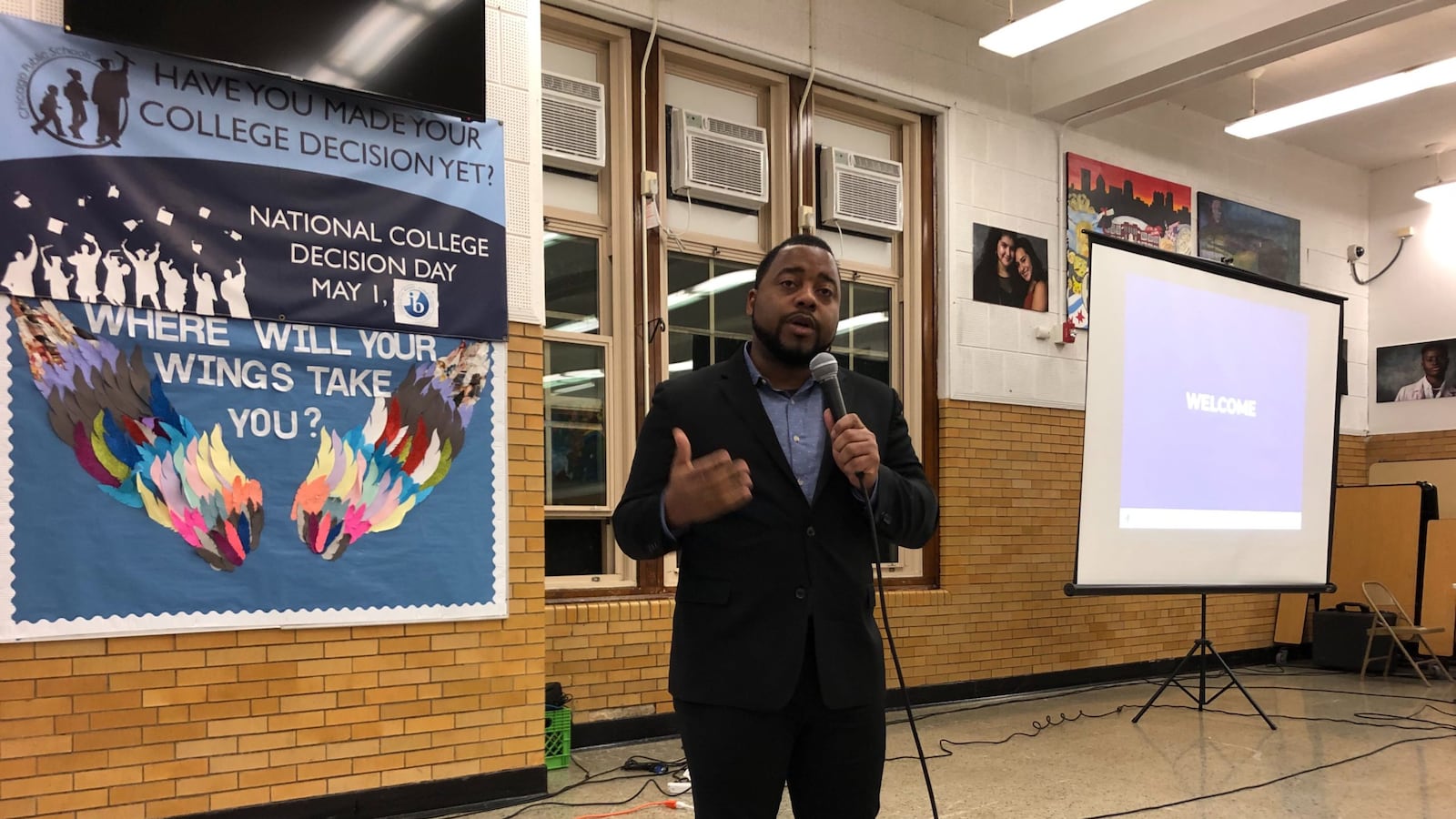

“How do we best support and align the work and the resource and the talent of our district to ensure that young people get what they need?” asked Maurice Swinney, who leads the district’s equity work.

In small groups, the participants brainstormed ideas and the budget work itself.

Among the suggestions: pattern school funding after Illinois’ system, which weights according to student need; educate parents on how money is spent so they can better advocate for school needs; eliminate money for special programs like International Baccalaureate or science-technology (STEM) schools; and hold a storytelling event between schools with resource disparities.

People acknowledged that the room had a significantly larger proportion of white people than the district itself. They also noted that students, principals, and support staff were largely missing.

After the public meetings, the school budget committee will recommend how to make next school year’s budget more equitable. It will hold more public meetings next school year.

Of the district’s budget, 57% comes from local funds, 32% from the state, and 11% from the federal government. But Chicago Public Schools falls about $1.9 billion short of what the state considers adequate funding. That means it needs about $5,000 more per student to properly serve student needs.

Participants wondered, how effective could a new formula be if the district didn’t have more money to spend?

Andrew Askuvich, whose two children attend Jamieson Elementary School in North Park, said the meeting underscored how Chicago schools are underfunded.

At Jamieson, the parent organization raises enough to offer each teacher about $300 for school supplies every year. That’s less than schools that fund teacher positions, Askuvich said, but it’s more than what many schools raise.

“In the end, there’s the understanding that there is just not enough right now,” he said. And if the district does get more money, he said it should go to schools with the highest needs first. “For a lot of people [here] it was really about equity, about making sure the schools that have been neglected for decades, that more is done for these schools.”