For educators like Margarita Mojica at East Moline School District 37 —which is close to the Iowa border — the school year has had a rocky start.

The district planned to start in early August but had to push the date back to Aug. 17 because a windstorm knocked out the power for three days. Families and the district experienced power outages and limited access to internet service. Then, a hybrid plan that involved some in-person learning was scrapped for an all-virtual start when the number of COVID-19 cases spiked in the area.

Though the initial weeks presented many challenges, Mojica has been persistent in pressing ahead despite technology glitches and building connections with students who are learning English. As a Spanish bilingual transitional teacher for seventh grade at Glenview Middle School, Mojica draws on her 25 years of classroom experience and her own upbringing as the daughter of Mexican immigrants to celebrate the cultural diversity of all of her students.

This year, she was a recipient of the Golden Apple Award for Excellence in Teaching.

During an interview with Chalkbeat, Mojica talked about the challenges of remote learning, how she is still incorporating culture into her classroom, and how she is helping her students navigate a year that has brought a pandemic and protests following the killing of George Floyd.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How are you feeling about the current school year?

I’m feeling like a lot of other teachers: where it’s so much new that we’re learning as we’re going. There are days that I feel okay. There are other days where the technology glitches. Some days there is a lot of frustration because you think, ‘If we were in person I could do it this way, I can help the student out.’ I do take solace in knowing that I’m not alone. I have my colleagues to lean on and turn to and that’s helped tremendously.”

What challenges have you faced so far, while teaching in your subject area, this school year remotely?

I’m co-teaching math, language arts, science, and social studies. The biggest challenge that I have is that I’m not able to meet with all four of the teachers. When we’re in the building together, we can sit down and look at the material together.

Since I’m a transitional bilingual teacher, during class it kind of feels like I’m playing ping pong with a colleague. They will share some information to students in English and then I translate that into Spanish. Whereas if I were in the classroom, it’s a bit more natural to speak two languages. Speaking to a screen is not natural.

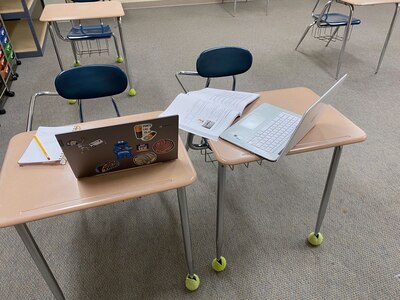

What does a typical day look like for you now?

My day starts at 5 a.m. I’m in the school building by 7 a.m. Between 7 a.m. and 8 a.m., I go through our Google Classroom to see what’s posted and if everything is in Spanish and English. I see if there is something that I need to have a heads-up about that is coming in one of the classes. I clarify lesson plans with a colleague and answer emails from students.

From 8 a.m. to 9 a.m., I have office hours. I work with three students who have recently arrived in the U.S. Although the work is in Spanish and English for math, language, arts and science — the curriculum in social studies is not. That’s the area that we’re focusing on together. At 9 a.m., homeroom begins. From there the day doesn’t stop until the end at 2:45 p.m. I have had to say at 2:45 I have to walk away just for my own mental health and to be as productive as possible for the next day and not burn myself out.

What challenges do you face teaching English Language Learners remotely? What advice would you have for educators in a similar position?

Since we’re co-teaching together, both languages are valued and used in the classroom. It’s not a word-for-word translation. My co-teacher and I are starting to get our rhythm, where the students are starting to understand the information that is presented to them, and it is presented in a way that is not too fast. The students know that they can ask a question in Spanish or English.

With a teacher who is on his or her own and does not know, in this case, Spanish, I can understand the difficulty. That’s where I’d say that pictures and videos help a lot. You do the best you can on screen but there’s nothing like being in person when that’s needed.

What has been your favorite lesson to teach remotely and what about it works well?

When I incorporate our culture into a lesson. In language arts, we are speaking about figurative language and enriching our writing. My co-teacher did a very nice job of sharing some rich writing about white water rafting, but there wasn’t a lot of response from the group of students that I work with. The next day, I presented a book called “Salsa,” which are bilingual poems about growing up Latino in the U.S. I found a poem about mangoes and the kids connected to it; they could tell me about the taste and the smell and the feel of a mango. To see the words presented in Spanish and in English, it was really nice for them to see their language being celebrated.

After months of isolation — and in some cases grief and trauma — there’s been a lot of talk about the importance of social-emotional learning this coming school year. Will you be doing anything differently this year to account for what so many families have been through?

Our counseling department does put out social-emotional learning lessons that are shared out in our homerooms — as well as a Google Classroom —for every grade level for each student to check in. For my students, I ask them, ‘How are you doing today? How are you feeling today?’ It’s not purely academic because I want to know what’s going on. When I call students’ homes, I ask them, ‘How are you doing?’ and there are times that there are issues that need to be addressed before learning like if they’re in need of food, if there’s an issue with internet connection or if there’s an issue with a device that they have. We want to address that.

Have you talked to your students about the antiracism protests that took place following the police killing of George Floyd?

I did have conversations with my students in the spring time when I wasn’t co-teaching, so it was just my class. Even before we had school closing, we’ve had those conversations. In my classroom, I had students who were African and Afro-Latino as well. There were issues that were affecting us as Latinos, and continue to affect us as Latinos, and our room was a room where those conversations could take place. The kids just needed to talk about it and ask questions.

In the fall, my students wrote postcards meant to uplift young people who were being held in the detention camps in the United States that were traveling up from Central American. I think it was therapeutic to the students that were in my classroom, who were also held at the detention camp, and they felt safe enough to share their story with us.

Tell us about your own experience with school and how it affects your work today.

My experience at school wasn’t easy. I was on my own. I did have three older sisters, but they were facing their own challenges because we were all the first to go to high school and college. We all tried to understand the system, navigate it and try to succeed. It wasn’t easy. At a certain point I wanted to just stop. The reason I kept going is because I didn’t want to bring shame on my parents. They immigrated from Mexico to give us this opportunity, To be the one that threw it away, I didn’t want to be the one to bring shame to them. That’s what kept me going and what keeps me going to help others who are like my parents who came to this country wanting a better future for their children through education because that’s what opens doors.

What’s the best advice you ever received — and how have you put it into action?

There is a book that I have and I think I’ve had it for 20 years. It’s in Spanish and English. It’s called “Un Canto Azteca.” It is an Aztec chant that actually comes from the Toltecs of what is now called Mexico. It’s advice that they give at different stages in life and then the Aztecs incorporated it into their culture. It teaches you how to carry yourself, to remember who you are, and to apply yourself to do the best that you can. It makes me think that my ancestors are giving me this advice for today. Also, I use the four agreements that come from the Toltecs which says to be impeccable with your work, don’t take anything personally, don’t make assumptions, and always do your best.

What gives you hope in this moment?

My students give me hope. We just need to make it through this pandemic. We are keeping ourselves informed about staying safe and healthy. So that when this passes, and it will pass, that we are stronger and we continue to grow. These students will make it. I just ask that they hold that door open for the next students.