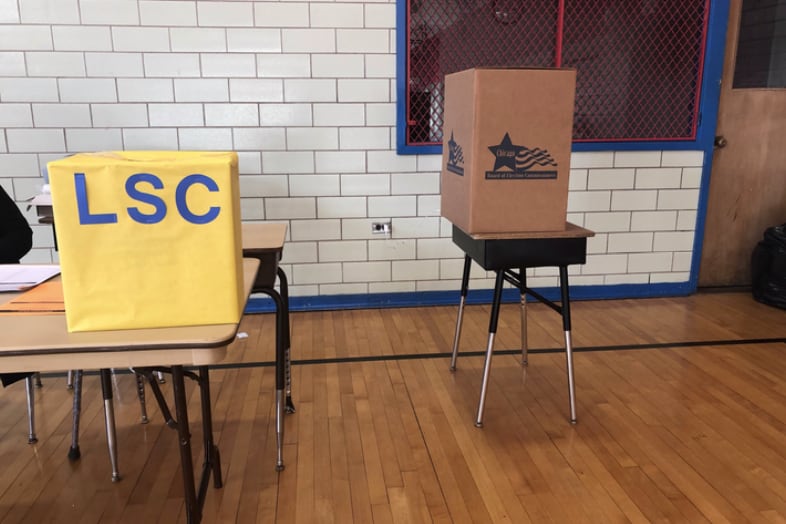

Despite much anticipation and perhaps because of pandemic fears, polling for school council at one Chicago school Wednesday drew few voters. Election judge Margarita Cruz mostly presided over an empty gym at Richard Yates Elementary in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood.

“I’ve only had six voters today, and all were teachers,” said Cruz, who has worked city elections since 1970. She was called to fill in for a sick judge — a reshuffling that delayed the start of the Yates election by 2½ hours. “None have been parents — not even one.”

Yates’ Principal Israel Perez sent robocalls, text messages and emails to the families of his 330 students about the biennial elections. Perez said he hoped he’d still get mail-in ballots — parents have until Nov. 30 to drop off ballots at schools — but so far he hadn’t received a single one.

“People are scared,” he said, as cases of COVID-19 rise precipitously and health officials have warned people to stay home.

Still, he praised Chicago Public Schools’ massive undertaking: to rewrite the election rules to establish a mail-in option and curbside voting, and send ballots to hundreds of thousands of families.

“What the district has done by allowing people to vote at home is really awesome.”

Voting for school council matters because the mini-democracies are able to hire and fire principals, make budget decisions, and, at some schools, decide on whether to keep stationed officers.

Chicago Public Schools leaders tried at the start of the year to stoke enthusiasm for Local School Council elections. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. A coalition of parent groups and civil rights attorneys now say the district was underprepared for the election, leaving too many parents and community members unaware and jeopardizing the integrity of election by not ensuring ballots were printed correctly nor communicating how votes will be counted safely and securely.

Elementary schools voted Wednesday, and high schools will vote Thursday. Chicago schools chief Janice Jackson said Wednesday that she hoped a record number of candidates would draw a record number of voters. “The next two days are extremely important for the Chicago Public Schools community,” she said.

The results and voting data won’t be in until Dec. 1. But early reports signaled challenges at some campuses and a smooth voting experience at others.

By late afternoon, a hotline set up by the Chicago Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights had received about a dozen calls about delayed poll openings, misprinted ballots, and general confusion.

“The big theme of day has been a basic lack of planning from CPS — something we were concerned about and the reason why we sent so many advocacy letters,” said Timna Axel, the director of communications for the lawyers committee.

A spokesperson said the district developed a staffing plan, with backup judges at the ready, to ensure polling sites were operational, and contested any reports of understaffed polling locations. It also staffed a command center to support election polling sites throughout the day.

Still, voters said variously they mistrusted the mail-in ballots and didn’t see enough candidate information online.

Councils were required to hold virtual candidate forums, and encouraged to put up candidate statements.

“There was a forum in October, but there are no statements and no recording that I can find,” parent Elizabeth Dowling said. “There’s nothing on the school Facebook page or webpage. Should I vote so blind? I don’t know.”

Troy LaRaviere, head of the principals association, told the school board Wednesday that the district didn’t provide principals enough support to run the elections at their schools. Some lacked election judges.

“They are telling principals to ‘just make it work,’” said LaRaviere, a former principal and frequent critic of district policies. “Do you have any idea how much frustration, anxiety and stress you are creating?” he asked the school board Wednesday.

A handful of voters who cast their ballots Wednesday said they found the process straightforward and mostly safe.

Tim Lacy, the chair of Swift Elementary’s council, said he found voting to be quiet and orderly at school, though he did see an election judge not wearing a mask inside the building.

Lacy, who is running for his second term, said he hoped to make the council, in the Edgewater neighborhood, more welcoming to immigrant and refugee families. But with little translation available, the council relied on the school’s “Friends Of” group to handle most outreach to those families.

Established in 1989 to provide parent and staff input into the running of schools, Chicago’s Local School Councils were heralded as a way to empower communities. In recent years, participation has fallen off and some members have complained of lack of training training or resources to effectively wield their power.

This year, elections drew 5,910 candidates, a 4.5% increase over last year. The number of seats without a candidate declined to 696, a 21.4% drop.

Still, Axel, of the Lawyers Committee, said she’s worried.

“Folks are not participating because they don’t trust that their vote count, that they are going to be able to vote anonymously and without reprisal, and, at some schools, that they are going to be physically safe,” she said.

“The lack of engagement is the more tragic part of this whole thing.”

Chicago Public Schools said it did not have any preliminary numbers on first-day turnout but that “many” community members voted both at the polls and curbside.

Counting will begin at schools on Dec. 1, and vote challenges may be filed from Dec. 2 to 4. New council members will begin their terms on Jan. 11, and serve for 18 months.

Natasha Erskine, parent organizer with Raise Your Hand, said that among the difficulties, she saw bright spots: a significant number of new candidates and positive energy among voters. “Folks are out there doing what they are doing in their cute masks and participating in this democratic process.”