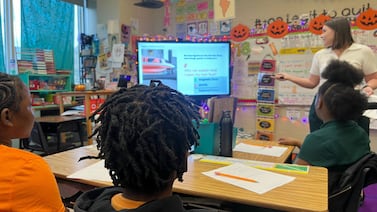

This fall, Emily Fitch, a teacher at Chicago’s private Morgan Park Academy, found herself in a position for which her training had not prepared her: About a dozen students were in her sixth-grade classroom, while another half-dozen were on a computer screen, tuning in via Zoom.

Fitch grappled with pressing questions: How could she best engage with both groups of learners at the same time? How to ensure her “Zoom kids” were heard and recognized in the classroom, making them feel they were fully a part of the learning experience?

Chicago Public Schools’ gradual reopening plan for early 2021 calls for this same approach of teaching in-person and virtual learners simultaneously, and the teachers union is pushing back, arguing it will shortchange students in both settings. But simultaneous instruction, as it’s called, is fast becoming a fixture of the return to school buildings nationally. Some educators at Chicago private and parochial schools that adopted the model this fall say it can work, but with some key supports, including technical upgrades and extra prep time for teachers. These campuses tend to have smaller class sizes and more resources than the city’s public schools.

Robert Pianta, the dean of the University of Virginia’s School of Education and Human Development, said simultaneous instruction puts unprecedented pressure on educators, who are largely left to improvise in the absence of research or established best practices. Yet, as more schools reopen — with some families bound to stick with remote learning and with districts facing staffing constraints — the approach appears here to stay.

“This is likely to be the primary mode of delivering education services in the coming months,” Pianta said. “We should be mobilizing resources to make it the best it can be.”

At Morgan Park Academy, Fitch said she still worries every day whether she is dividing her attention equally between students in class and on Zoom. But she said she and her colleagues have put a lot of thought and effort into making the most of the setup.

“We want to make sure everyone feels engaged,” she said. “I’ve learned a lot along the way.”

A steep learning curve

Word that Chicago plans to shift to simultaneous instruction drew a strong reaction from educators and the district’s teachers union, which has been a vocal critic of the district’s reopening plans since the summer.

Union leaders expressed skepticism that the method can work in a virtual town hall the union hosted for parents last week. Educators decried it on social media, saying the approach will put both virtual and in-person students at a disadvantage and could be a step down from the all-online instruction the district has offered since March.

Kathi Griffin, the president of the Illinois Education Association, also took aim at the method on WBEZ last week, saying she does not believe it is “effective for anyone.”

In an interview with Chalkbeat last week, Chicago schools chief Janice Jackson said she understands the questions and anxiety about simultaneous instruction, but said her team has deemed it the best option for now, given that the district has promised parents that their children can continue to learn remotely if they choose. She vowed again the district will provide professional development for teachers and lean on the lessons of schools across the country that have used the approach for months.

“I don’t want people to think that I don’t understand that this will be a steep learning curve,” she said.

Administrators at private and parochial schools in Chicago affirm the learning curve is indeed steep. About 55% of the Archdiocese of Chicago campuses are providing simultaneous instruction, at least in some grades, said Phyllis Cavallone, the archdiocese’s chief of academics. Other archdiocese schools were able to assign dedicated virtual and in-person teachers, sometimes by combining grades. In a few cases, when only a small fraction of families chose to stick with remote learning, schools enlisted an outside vendor to provide virtual instruction.

It’s not yet clear how much flexibility Chicago schools might have to offer dedicated classes for virtual and in-person learning, depending on the number of families who choose to keep students home. Jackson said that all teachers must return to school buildings unless they request formal medical or family leave.

Cavallone said the archdiocese gave schools leeway about how to set up their simultaneous learning, but across the board, the transition was difficult. There was a push to upgrade bandwidth in school buildings as sluggish connections were an early hurdle for some educators. Schools provided teachers with microphones as some quickly realized their “teacher voices” would not do.

“We did a lot of, ‘Hey, it’s OK to change things up and learn as we go,’” she said. “Nobody went in hitting the ground running. None of our education programs in college ever prepared us for this.”

At Morgan Park Academy, about 40% of students continued with remote learning when the campus reopened in August, though in the early grades that percentage was significantly lower. The school switched to all-virtual learning in early November when a COVID-19 case quarantined its maintenance crew; the school, which began the school year early and eliminated as many days off for students as possible, is on winter break now, but plans to return to campus in January.

To make simultaneous instruction work, the school also upgraded its wireless network to allow more than 50 teachers to livestream from classrooms, ensured document cameras and smart boards worked in each classroom, and provided training and simulated classes, said Vincent Hermosilla, the assistant head of school.

Chicago Public Schools doesn’t have the same resources at its disposal as some of the city’s private campuses, and, at many of its schools, class sizes are significantly larger than those on archdiocese campuses. With budget constraints and in the absence of additional federal stimulus funding, Chicago may not be able to readily purchase additional equipment or offer dedicated tech support in each school.

Pianta, the University of Virginia dean, said while he has seen some preliminary case studies on simultaneous instruction, there is no systematic research, meaning schools are left to improvise as they navigate this uncharted territory.

He said engaging students and monitoring their work remotely is already challenging, and doing that while also teaching in person compounds the hurdles.

“They are essentially teaching two classrooms in two different ways at once,” Pianta said. “We have heard from teachers that they ultimately end up focusing on one group or the other.”

But he said with simultaneous instruction a virtual inevitability in the coming months, districts and schools can take key steps to support their teachers.

Districts with robust curriculums will have an easier time adapting lessons to those new demands. Extra time for planning is crucial because educators need to prepare lesson plans and learning activities for both their online and in-person students.

“When teachers are given that time,” Pianta said, “those are the most successful examples of this by far.”

What has worked

At Morgan Park Academy, Fitch said she’s made adjustments in the course of the fall.

She stopped wearing a headset, which meant that students in the classroom could not hear their peers tuning in virtually. Instead, she now only uses a microphone, sometimes repeating questions or comments from students in the classroom who sit farther in back for the benefit of the virtual students, who are projected on a smart board for their peers in the classroom.

Like many of her colleagues, Fitch has also figured out that for parts of the class, it makes more sense to train the camera on students in the room rather than on her, so the two groups of sixth graders can engage with each other during classroom discussion.

“I’ve wanted to make sure these kids felt a connection to the classroom,” she said.

Fitch said having the school’s tech team available throughout the day has been enormously reassuring: Once, when her camera stopped working, a staff member rushed to her classroom and fixed it within minutes. And she said she definitely spends more time on preparing for classes.

Hermosilla said teachers like Fitch have experimented and innovated throughout the fall. Some have set aside time for their in-person students to get on Zoom and work in small groups with their peers learning from home. For the school, replicating the hands-on, project-based learning that’s a cornerstone of its model has been especially challenging. But whereas virtual students might have to just watch their fellow students conduct chemistry experiments on campus, teachers have tapped them to take notes and work out the relevant chemical formulas so they feel more included in those activities.

“It worked surprisingly well,” Hermosilla said. “Teachers came up with ways of really leveraging the technology and making it happen.”

At the archdiocese, Cavallone said some schools have embraced a technology named Owl that allows the camera to follow teachers as they move in front of their in-person classes. She said the archdiocese has encouraged, though not required, more prep time for teachers, and some schools have tweaked their schedules to allow it.

Chicago Public Schools’ reopening plan says teachers who provide simultaneous instruction will get two additional hours a week to plan. The Chicago Teachers Union, which raised teacher prep time as a key issue during last winter’s strike, could end up pushing for more. Tensions remain high between district leaders and union officials, who have charged the district with failing to negotiate with them over reopening and this week sought to block the reopening bid in court on those grounds.

In archdiocese schools, key improvements have bubbled up from engagement with teachers, Cavallone said.

“Listening to teachers is really important,” she said. “What they have done this year is absolutely phenomenal.”

Cassie Walker Burke contributed to this report.