Chicago school officials bristled and responded critically Wednesday to the city’s outgoing inspector general, whose latest report documented irregularities in the high-stakes annual tests administered to students.

Board members and administrators maintained that test scores reflect higher achievement and disputed Inspector General Nicholas Schuler’s analysis that the report indicated some cheating and gaming of the system.

‘The district has exhibited real, sustained academic progress, as noted by numerous independent studies… all of which have come to conclusions using a variety of metrics and assessments other than NWEA, ” Chief Education Officer LaTanya McDade said, referring to the state test.

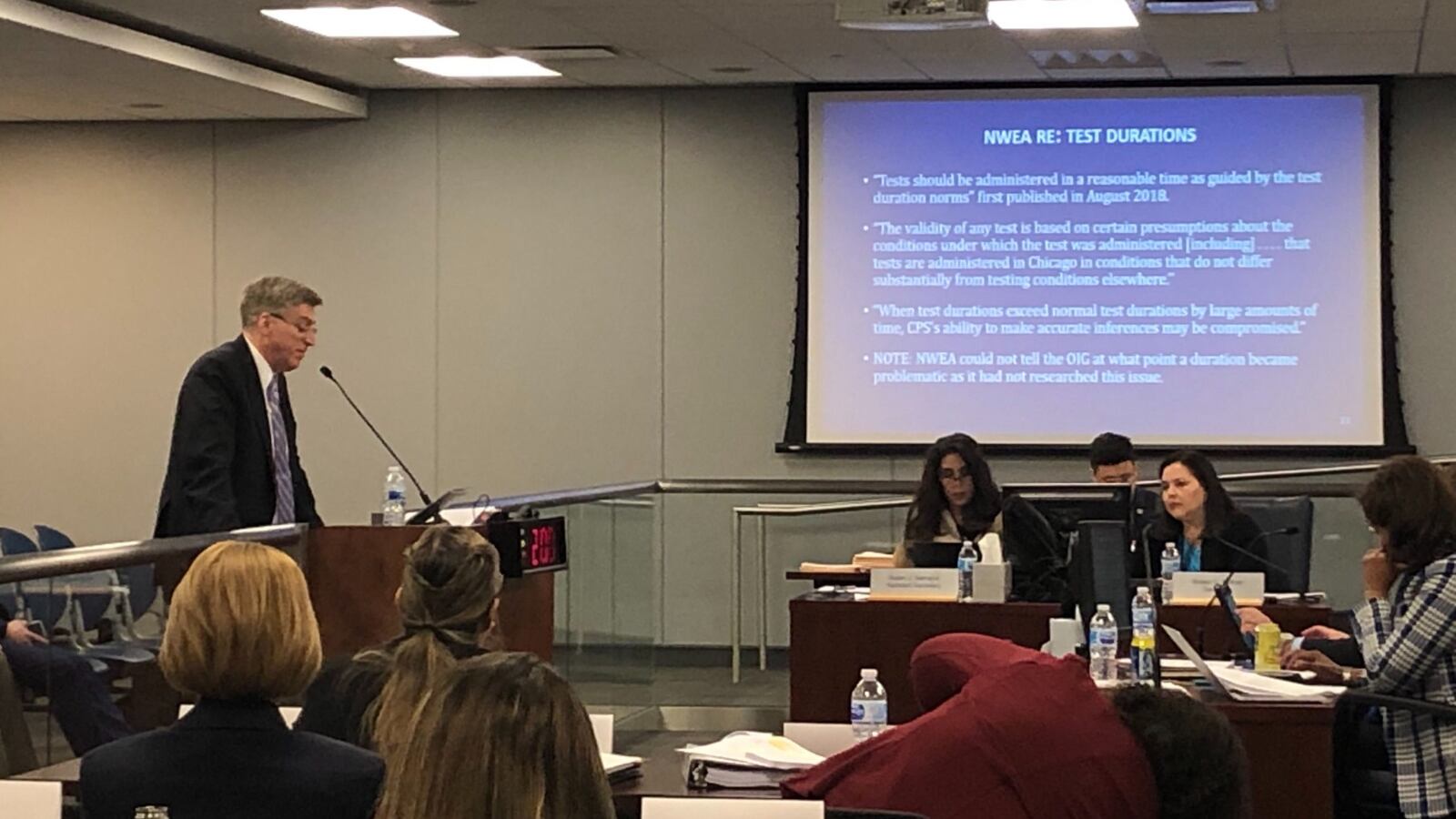

In his last board meeting before leaving his post, Schuler formally presented a report on Wednesday showing irregularities in the administration and scores of a high-stakes test for third through eighth grades. Test results affect school ratings, teacher evaluations, and admissions to selective enrollment high schools.

Two years in the making, the report found a dramatic difference between the amount of time Chicago students took to complete the untimed test known as NWEA/MAP during one testing cycle and the average time nationwide, and signs of unusual test pausing. Both discrepancies could “be an indicator of cheating or of attempts to game the test,” according to a report provided to the Chicago Board of Education.

In response, district officials strongly disputed the idea that cheating took place, saying Schuler had not provided sufficient evidence. Leaders also insisted that the testing irregularities did not negate the academic gains that Chicago schools have made in the past decade.

Even so, officials acknowledged a need for more clear and consistent oversight on the NWEA. Administrators said they would adopt the majority of the report’s recommendations including defining a time limit for the test, more closely reviewing how it is administered, hiring a testing security firm, prohibiting teachers from being the sole person overseeing a test on which they are graded, and reevaluating all the district’s standardized testing.

A few new details from the report emerged at the meeting. The average time Chicago students spent on the test got progressively longer from 2016 to 2018. To help understand what took place at schools, the Office of the Inspector General interviewed 20 students and 10 teachers.

One seventh grader told the investigators that her classmates would rather let a question time out than guess and be wrong. “We were so worried about high school,’’ the seventh grader said, since NWEA scores are part of a student’s admissions portfolio for the district’s selective enrollment high schools. “Guessing — we would never do that.”

In analyzing test results the report found long tests had a “strong relationship” with unusual growth in achievement.

But district officials said the results didn’t show a correlation between duration and academic growth.

Several board members appeared visibly frustrated by the term “ cheating,” even as Schuler protested that he had not meant to suggest widespread and deliberate wrongdoing, but was instead pointing to some discrepancies.

“It’s a serious accusation to our teachers, students and school communities, and I don’t see the evidence here, ” board member Elizabeth Todd-Breland said.

“It feels irresponsible,” board member Amy Rome said.

Board members were particularly concerned that the report could be used to downplay the work of students and teachers in communities of color. “You have taken away the hard-won credit of the school,” said Lucino Sotelo.

In response, Schuler and his team said some cheating was possible. “It would be naive to think that is not in the mix of possible situations, ” he said.

But, at the end of the day, he said that his team didn’t have the capacity to seek out widespread wrongdoing. Instead, the report, his last as inspector general, was an effort to push change in a high-stakes test. “If you take the cheating out of it, we are still facing serious questions about the validity of the test,” he said.

The NWEA test will next be administered this spring, and the district’s contract with NWEA expires in June.