At Vanderpoel Elementary Magnet on Chicago’s South Side, educators are strategizing about when to schedule live video instruction and training parents how to navigate the district’s digital platforms.

Across the city at the North Side’s Amundsen High, teachers are learning how to make lengthy stretches in front of computer screens more interactive and engaging.

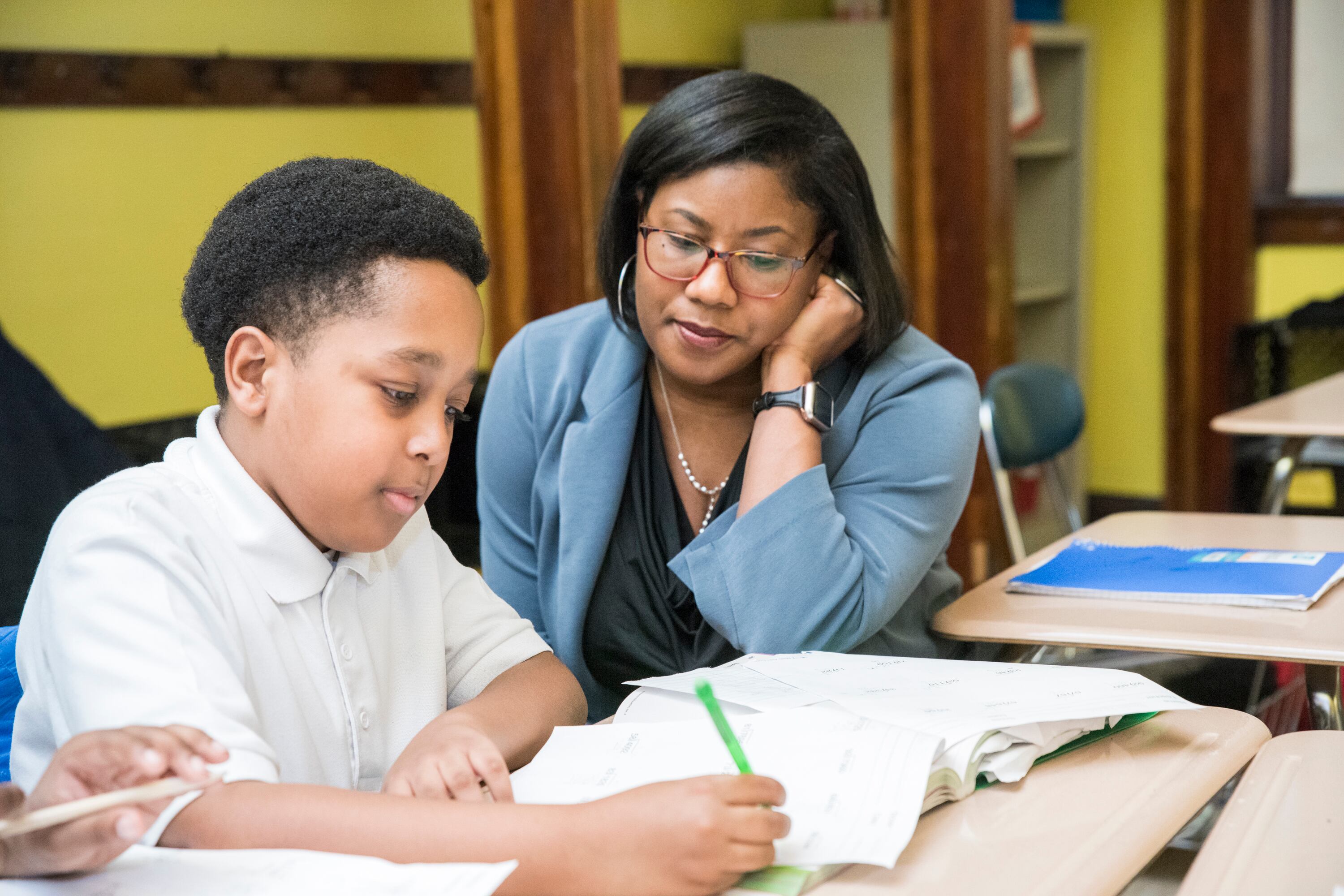

Chicago unveiled earlier this week a more detailed plan for all-virtual learning this fall — what leaders described as a bid to increase accountability and raise expectations for both students and educators. Now, school leaders and educators across the city are wrestling with how to build a six-hour virtual school day — an endeavor that calls on teachers to keep their students’ attention remotely longer than ever and enlists parents as key aides, especially during hours of independent work built into each day.

The guidelines require schools to provide more live video instruction, from an hour in pre-kindergarten to three hours in the early elementary grades to 80% of the school day for high schoolers. They also herald a return to business as usual in grading and attendance, along with annual evaluations for teachers.

For Chicago’s campuses, the plan leaves key details to iron out ahead of the Sept. 8 start of the school year: How to set schedules and structure the school day to increase the odds that students will stay focused and engaged? What, if any, printed materials and supplies to distribute to students at a time when a new digital curriculum the district is rolling out is taking center stage? How to add checks and balances to deliver on a promise of a better experience for students this fall?

The Chicago Teachers Union, which already filed one of a planned string of grievances against the fall plan, says the framework puts schools in a tough spot. The union argues that the district is trying to squeeze a regular brick-and-mortar school day awkwardly into a digital mold instead of innovating to make the most of virtual learning. The result: too much screen time and too little grace for students, parents and teachers still grappling with the fallout from the pandemic, union leaders say.

At Vanderpoel, principal Kia Banks says fall will bring fresh challenges — ones her team is working hard to anticipate and tackle.

“Once we get over the shock of this, we have an opportunity to change what public education looks like for the better,” she said. “My staff and I are taking an optimistic approach.”

Structuring the digital day

Banks says that as the parent of a third-grader and an educator, she worries about the amount of time students, who already turn to screens for entertainment and communication, will spend learning in front of their computers. As a former reading teacher, she believes younger students especially need to engage with the printed word.

But she said she and her staff are putting a lot of thought into how to make the virtual school day work as well as possible. This fall, students will log on to one Google Classroom site for the day rather than clicking on different links to connect with various teachers — digital transitions during which the school found last spring it was losing too many students.

Vanderpoel is also timing live instruction based on when students are most focused and game to learn: earlier in the morning for the early grades and mid- to late morning for older students, with more independent work and teacher virtual office hours in the afternoon.

The school is building in breaks and enrichment activities — music and dance classes from community partner Beverly Arts Center or downtime with the school’s yoga teacher — to break up the intensity of screen learning.

At Amundsen, Principal Anna Pavichevich is confronting a similar challenge and working with teachers to build in as much student-led time as possible.

“It’s hard to be on the computer for seven hours and be actively engaged,” she said. “We expect students to have some brain fog and some burnout.”

The key will be making that time as interactive and student-led as possible, she said. The school is setting a goal of students speaking and engaging with each other for 70% of the live instruction time, with teachers presenting to them for only the remaining 30%.

With a focus on building relationships remotely, the school will also host virtual clubs and step up efforts to provide mental health support, with counselors and nurses “pushing into” digital classrooms to watch for students who are stressed and overwhelmed. A post-secondary team is working on a plan to guide the school’s college-bound juniors and seniors, denied the chance to pop into a counselor’s office for application advice or grab scholarship materials in a hallway.

“This time, we’ll try to mirror the academic experience students had with in-person instruction,” Pavichevich said. “We’ll still be exercising a lot of grace and empathy, but the clear expectations will be there.”

Business as usual?

The Chicago Teachers Union has pushed back vocally against the idea of returning to normal this fall because leaders believe it ignores the ongoing reality of a deadly pandemic and puts too much of a burden on both teachers and families. On Twitter, they have embraced the hashtag #GruelingSchool.

Three hours of live instruction online for kindergarteners and first-graders are not age-appropriate or reasonable, says the union’s chief of staff, Jen Johnson. She said teachers are called upon to prepare daily for both their live video lessons and for small-group and independent activities some of their students will be doing simultaneously.

“You have too much screen time and not enough prep time,” she said. “You can’t impose in-person school on at-home learning.”

The union pitched a week of educator outreach to parents modeled on a Smart Start program the Los Angeles school district crafted in tandem with teachers. The idea is to provide coaching to parents on how to help guide learning at home, build relationships, and visit homes to drop off school supplies. Johnson said the district declined to negotiate over that proposal.

“We don’t feel we are using creative thinking to get students, parents and educators on the same page,” she said.

She said some schools have tried to provide training to parents and distribute supplies, but those are piecemeal efforts rather than a systemwide push. Detailed guidelines on special education and English learners have not been publicly shared yet. The union charges the district has not provided adequate “infrastructure” to both students and teachers, who the union says are in some cases paying out of pocket to buy camera tripods and other technology and to upgrade their internet.

Chicago schools chief Janice Jackson insisted this week that the expectations spelled in the plan are needed to improve education quality this fall. Tracking student and teacher attendance and evaluating educators are a necessary piece, she said.

“We are unwilling to reduce the amount of instructional time for our students; they have lost so much already,” she said. “We are unwilling to take accountability out of our system when our students and families deserve that.”

Banks said she and six other principals at schools in Vanderpoel’s area banded together this summer to plan and troubleshoot. They joined forces on teacher training and shared ideas on scheduling. This week, they are providing joint parent training on navigating the district’s digital platforms.

She said campuses are making school-by-school decisions on what printed materials and other resources to provide as the district is unveiling a fully digital curriculum it was in the process of developing when the pandemic struck. Her school will hand out books and supplies to its students.

The union and some students have also voiced concern that a return to pre-pandemic grading and attendance is premature and could breed inequities for students of color and low-income students, whose families have been hit harder by the pandemic. The district has said a sharp increase in student participation after it shifted to a stricter grading policy last spring vindicates its approach.

Banks said her school will work to strike a balance between more student accountability and a flexible, compassionate approach. Teachers will give students opportunities to make up work they missed and redo assignments; the school has formed an outreach team that will work with educators to connect with the families of students who are struggling.

Irma Orozco, a fourth-grade science and social studies teacher at Morrill Math & Science Elementary on the city’s Southwest Side, said even some of her best students struggled with motivation earlier last spring, when educators could not lower students’ pre-pandemic grades. Yet, she knows much can get in the way of learning, and she worries whether all students across the district will truly have access to the technology and internet they need to engage.

To mix up the virtual pace, Orozco plans to alternate between presenting lessons, doing science demonstrations, showing educational videos, letting students share out their assignments and engaging them in small groups — an especially key piece for her bilingual students.

Orozco says for the safety of students and teachers, an all-virtual start to the school year was the right call. She took workshops over the summer on how to better use Google’s digital tools and provide social and emotional support remotely. Though she feels better prepared for teaching virtually, she yearns for a return to her classroom.

“I think this is doable, but I feel bad for the students,” she said. “Kids are social beings, and need to interact with their peers in different ways — verbally, physically and emotionally.”