After being closed to students for 300 days, Chicago reopened campuses this week and ushered in a new era of schooling with temperature checks, classroom pods, health screeners — and a continued standoff between city leadership and the teachers union.

For some, reopening doors has caused them to fear for their safety. For others, it’s been a relief, injecting some normalcy into difficult times.

Interviews with families and educators on the ground reveal a mix of emotions and experiences that are intensely personal and also framed by race, class, and the COVID-19 rates of various neighborhoods.

Chalkbeat Chicago spoke to seven people at length about reopening school buildings this week for prekindergarten and some special education students who need extra support.

Here’s what we learned.

The cautious grandmother: Regina Simms

Regina Simms has taken a cautious approach to safety amid the pandemic.

Still, when her son’s family made the decision to send her youngest grandson back to the classroom at Dixon Elementary on Chicago’s South Side, she backed that wholeheartedly.

It was not an easy call for the boy’s parents: Her daughter-in-law, who works in the district, opposed sending the preschooler back, questioning if safety protocols would be followed faithfully. Simms’ son felt strongly the boy should go back.

Simms says her grandson this week quickly learned how to keep his mask on properly throughout the day and stay a safe distance from classmates. He reported he liked in-person school.

Simms, who is active with the nonprofit Community Organizing and Family Issues, which advocates for parents of color, says she understands the safety concerns surrounding reopening schools but feels all residents face a measure of risk.

“If you are concerned about catching the COVID-19, but you are not concerned about kids’ education, I disagree,” she said. “All these thousands of students in Chicago are failing like crazy. I’d rather for my grandchild to take a chance in school.”

The resolute mother: Cindy Ok, Vaughn Occupational High School

Until she began remote learning, Cindy Ok’s daughter would sometimes struggle with expressing herself. Then she found a new tool: the chat option in the Google classroom tool most Chicago schools use.

“If she doesn’t want to talk, she can just type her answer in the chat,” said Ok, whose daughter is set to graduate this spring from Vaughn Occupational High School. “She loves it.”

Still, Ok regrets that her daughter is missing the life skills classes she’d usually be taking at school right now, such as learning how to shop for food or develop leisure interests like visiting art museums.

Because Ok’s daughter is prone to seizures, those activities all felt unsafe amid the pandemic.

A positive experience with remote learning, along with an abiding fear of how COVID-19 would affect her child’s health, helped Ok decide that she wouldn’t send her daughter back to classrooms this winter, even though she only had a few months left at the specialized school.

“I would not send my daughter into school when there are students in her classrooms that come from ZIP codes that have a 17% rate of infection,” she said of Vaughn, which enrolls students from all over the city.

As school buildings have reopened, the first crop of school-based cases have occurred. On Wednesday, school officials at Vaughn announced that a person working in the school building had tested positive for COVID-19, but later said that staff member had not been in contact with students.

Still, the news only underscored Ok’s decision not to return her child to in-person schooling. “I still don’t think that one week after the winter break is a good time for anybody to go back in person,” she said.

The teacher in limbo: Marrissa Seidler, Burbank Elementary School

Every day since Chicago schools reopened this month has brought unanswered questions and logistical nightmares for Marrissa Seidler.

As a special education teacher recruited from outside of Chicago, Seidler lives in Skokie with her two children, and struggles with health conditions that she worries put her at higher risk if she should catch COVID-19.

She’s asked for several accommodations to work remotely that would address either her child care issues or health concerns, but hasn’t heard back on either. So far, Seidler says the stress of managing child care and waiting for answers has made her sick. She’s failed the health screener, required of all staff working in schools, several times and taken several sick days this week.

She’s extra frustrated because this week all her students have remained remote, but the district has said teachers must return to classrooms regardless of the choices their students make. She hasn’t been able to log on with them so far this week.

She misses her students. “It’s so hard to hear from my aides that they just aren’t doing what they should be doing,” Seidler said. “But I’m not going to put my health at risk. I have young kids: They deserve their mother.”

She’s not alone. Teachers with children are among the least likely to get accommodations from the district, according to data released this week.

The stress has her rethinking her future in Chicago Public Schools, which already struggles with a shortage of special education teachers. “They are going to lose high-quality special education teachers,” Seidler said.

The hopeful social worker: Brian Calhoun, Rogers Park and West Ridge

For weeks before schools opened, social worker Brian Calhoun studied the district’s suggested safety protocols, determined to follow them to the letter. When he returned to school, the walls featured posters and rooms had hand sanitizer stations.

What was missing? The students. “The big shock is that we have all these people reporting to the building, and so few students showing up,” said Calhoun, who works with special education students. “The most in one classroom is four students.”

The biggest challenge has been teaching students both online and in person, especially as the first wave of prekindergarten students are, simply, very excited.

“If I’m in a classroom and I haven’t seen [new] toys in a while, I am going to get up and get in the toys,” Calhoun laughed. He wishes the district had built an adjustment period into the first days of school.

Still, he is holding on to the good moments, like hearing a student who was kicking a ball outside for recess exclaim: “This was my best day!”

The excited father: Dave Wisneski, Vaughn Occupational High School

On Monday, the first day of in-person learning for students, Dave Wisneski’s daughter was dressed at 5:30 a.m. and brimming with excitement.

As a student at Vaughn Occupational High School in Portage Park, she’s among the students with complex disabilities identified as a priority to return to campuses.

So far, the first few days of taking the bus and chatting with school support staff, even if she still does most of her schoolwork remotely in the classroom, have given her much-needed social interaction, he said. “It’s been a great experience,” Wisneski said.

That contrasts with remote learning from home, he said. The more his daughter missed social interaction, the more she struggled to focus on the computer.

Wisneski, a newly elected school council member, applauded the district for bringing special education students who need extra support back first. “Kids with disabilities always seem to be left behind,” he said. “It’s great to see how we were the first ones invited back.”

The demoralized educator: Sandra Méndez, Southwest side

When the week started, Sandra Méndez and the other prekindergarten teachers from her elementary school on the Southwest side of Chicago were determined to resist returning to school.

Remote learning was tough, but Méndez felt that after nearly a year, she had found ways to engage her young students and build relationships with their families. The virus has decimated her school’s neighborhood, home to many essential workers. Only one student in her class of 10 had opted for in-person instruction.

“The whole week that we were out I had been thinking, how am I going to do it if I have nine kids on the computer and one kid in the classroom?” wondered Méndez. “I have one lesson I repeat at 9:30 and then at 10:30. That means that student that is in the classroom is going to listen to the lessons two times.”

Then, a few days ago, the district disciplined teachers who were resisting returning to school, by freezing their pay and locking them out of remote classrooms.

Méndez worried about losing her job and felt little support from teachers at her school — many who teach higher grades not set to return to classrooms until later this month. She overrode her fears and returned to campus.

“This is our future and it’s our career, and many of us don’t want to lose that,” she said. While she had enjoyed and appreciated becoming part of the union’s citywide organizing to oppose in-person school, she felt demoralized by the lack of support in her school. “They are probably thinking the same thing: we are not going to step in and jeopardize our jobs. It feels like we are alone right now.”

The newly energized math teacher: Sam Williams, Schurz High School

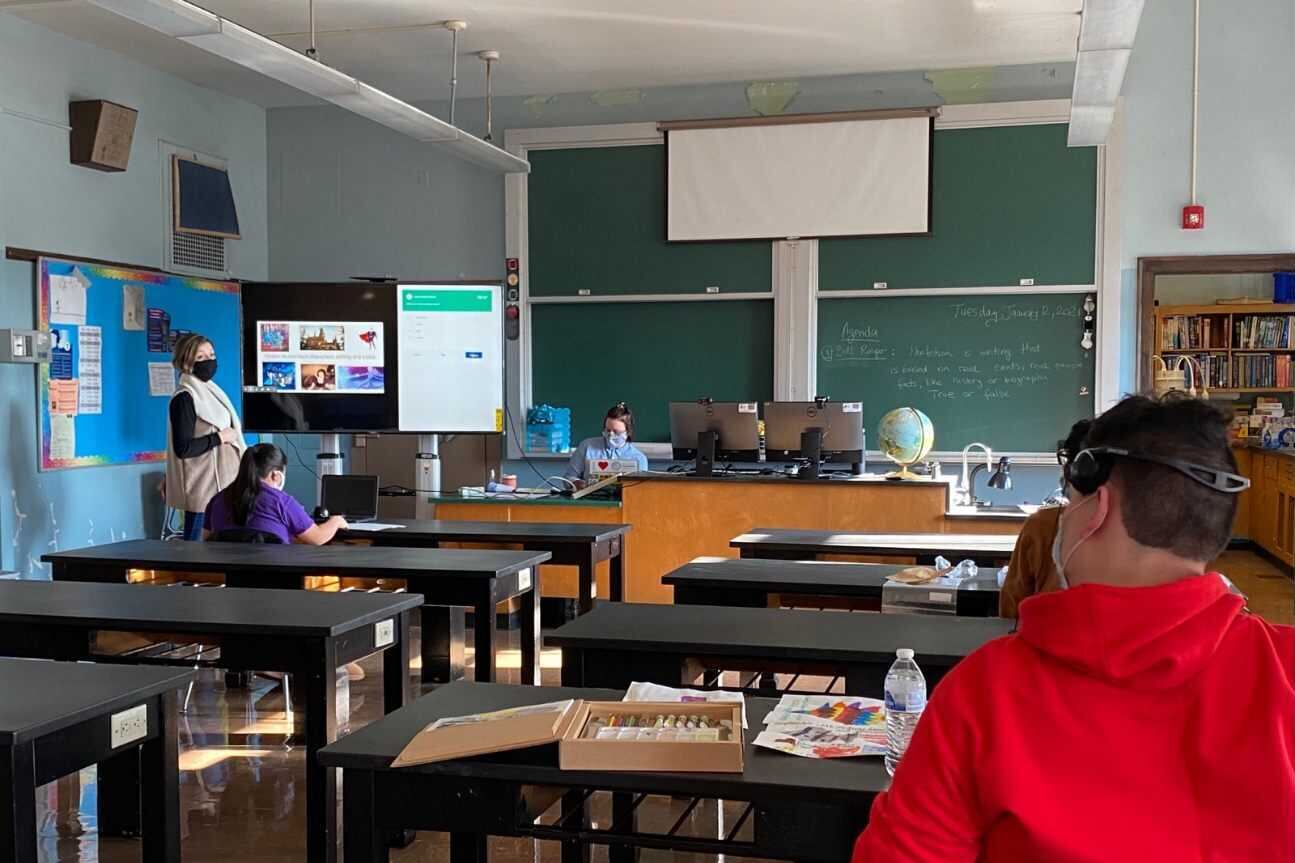

Even though Sam Williams has been working with her special education class of 12 high school students since the fall, she was surprised by how much easier it was to build a relationship with them in person.

“They are totally different students in person,” said Williams, who works in a classroom with two aides. “We are getting to learn about their behaviors, where they are at academically.”

Out of 47 students in the specialized program, 12 have returned, and were placed in two pods of six. Some special education teachers reporting to Schurz High School still primarily communicate with students remotely, to minimize exposing children to adults.

Her students have returned at all different levels, with some having spent months with assistance from an eager parent or sibling and others lacking any guidance. Now she must figure out who needs extra support in which areas, but Williams said the challenge has newly energized her.

She and her co-teachers spent six weeks putting together their learning plan, which already has required some tweaking. They record their lessons so they can more easily plan instruction for different levels in each subject.

Williams said she’s glad to have the flexibility to meet those needs — and to get to see some of her students face to face. “There is just something about being in the classroom that you can’t get at home.”

Mila Koumpilova contributed reporting.