On the evening of July 7, 2021, my 18-year-old stepson, Miles Thompson, was shot and killed behind his father’s house shortly after pulling into the driveway. He lay there overnight and was only discovered the following morning when his younger brother — my 10-year-old son — peered out of his bedroom window and spotted Miles’ body.

What happened in the hours and weeks since then has largely been a blur, but I have thought a lot about the assailants and what led them to that fatal moment. What was their mindset when they decided to open fire on an innocent young man? What put them on the path to violence? Who had loved them throughout their lives? Who had hurt them? What complex web of thoughts and events led to the night that would deprive Miles of his future and change our family forever?

What, if anything, could have been done differently?

Although the circumstances of July 7 are unlike anything that I’ve ever experienced, the questions that I’ve pondered since then are not new to me, and answering them has been my life’s work.

I am the president of Thrive Chicago, where my work focuses on providing youth from underserved communities — and particularly boys and young men of color — with the educational, social, and employment opportunities they need to live purpose-filled lives. As a teacher turned nonprofit leader, I spend my days listening to Black and brown youth and trying to understand their needs, desires, and challenges.

This work is not for the faint of heart, nor for those looking for quick fixes to the crises that Black and brown youth face. Despite the allure of gun buyback programs, lawsuits targeting gang members, and harsher sentencing, the need for “upstream” investments — education, job training, and mental health services — is as urgent as it has ever been. Between the pandemic, its economic fallout, and the anxiety that individual and systemic racism has spurred, communities of color need access to the relationships and resources that create a sense of belonging and reduce the likelihood of destructive decisions.

These investments take time, they take money, and they take a commitment to the long game that runs counter to the desire for immediate results. But if we believe in the potential of youth — regardless of their background or ZIP code — then we must be willing to challenge beliefs about who among us deserves support (and who doesn’t); who deserves safety (and who doesn’t); and who deserves a chance at a life full of opportunity (and who doesn’t).

In the days following Miles’ death, I watched as the media account of his murder shifted. Initial reports characterized him as an 18-year-old “man,” killed in an alley on the (dangerous) West Side of Chicago. Within days, he was described as a “teen” from the suburbs, and then as the all-American, suburban “kid” next door, full of promise before he found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time.

This shift — subtle but glaring — highlighted for me just how the stories we tell ourselves shape what we believe to be true about each other. It also underscored the implicit narrative that some of us are born to fly, while others of us are born to falter. In the case of Miles, I didn’t need the media to remind me of what a special person he was, and how deserving he was of a long and happy life.

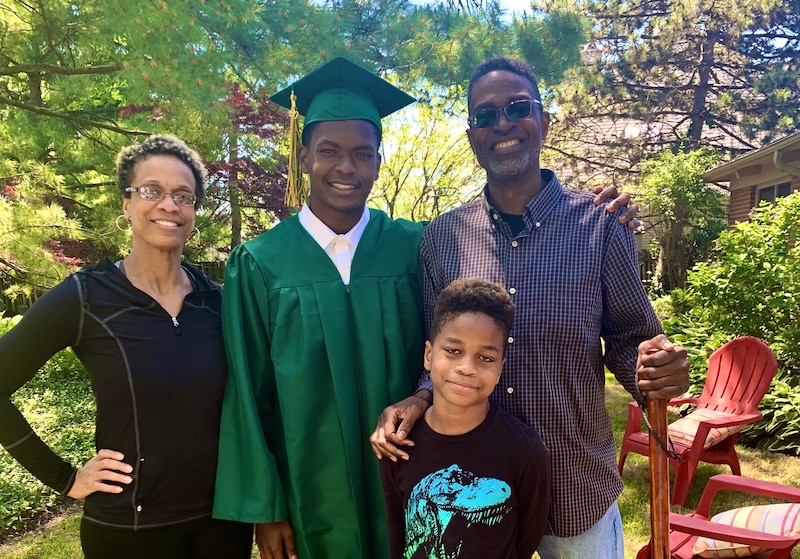

I first met Miles when he was just a few months shy of his fifth birthday and was proud to be part of the blended family of caring adults who loved and supported him right up until his death — just two days before his 19th birthday. During those intervening 14 years, I watched Miles grow and approach the cusp of adulthood as a person all parents wish their children to be: loyal friend, loving big brother, and protector of the underdog. He was a budding entrepreneur, full of ambition and bold dreams for the future.

Each day since his murder, I’ve wondered about the young men who killed Miles and who brought the worst kind of violence and grief to my family’s door. I do this even as I push in a professional capacity for programs and policies that give young people a chance to thrive.

I often ask myself if such efforts could have made a difference in the lives of those who took Miles from us? Could a collective of voices and effort have turned the tide? And then I remind myself that I am that voice. We are that tide.

This experience — as horrific and excruciating as it has been — has only redoubled my commitment to the young people of Chicago, to the resources and support that they need, and to the long game. It’s what we owe Miles. It’s what we owe all of the Black and brown boys like him and the promise that they hold.

Sonya Anderson is the president of Thrive Chicago.