Chicago Public Schools expects about 60,700 students in the elementary grades and in intensive special education programs to learn in school buildings by mid-March — slightly fewer than 30% of the eligible students.

That’s down from about 77,000 eligible students whose families indicated in December that they would opt for the district’s blend of in-person and remote learning in early 2021. That smaller group, which is more than two-thirds Black and Latino, remains disproportionately white. White students make up just under 13% of students in those grades but 24% of students returning to classrooms.

During the monthly meeting of the school board Wednesday, district leaders said they believe that some families who are holding back will opt for in-person instruction in April as they see the district safely reopen elementary school buildings. They also said negotiations will begin this week with the district’s teachers union on a high school reopening — with the goal of offering high school students an in-person option yet this school year.

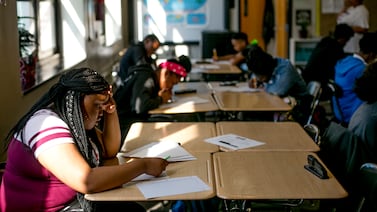

At the Wednesday meeting, officials also shared attendance and grading data for the school year’s second quarter. As they have done earlier in the year, they pointed to an attendance dip and a rise in failing grades, particularly for Black and Latino students, as an argument for forging ahead with school reopening.

“The takeaway from this sobering data is the need to reopen schools for students who want to come back,” said LaTanya McDade, the district’s academic chief.

In December, 37% of students in prekindergarten through eighth grade and special education cluster programs indicated they would opt for a blend of in-person and virtual learning. That group was 39% Latino, 30% Black and 23% white, while white students make up about 13% of students in those grades.

Turnout in preschools and cluster programs, which reopened for in-person learning in January, signaled fewer students than expected are likely to show up for next week’s second reopening wave. About 38% of students in those programs had said they would return to classrooms. In fact, only one in five did. Those numbers again pointed to a racial divide, with white students in that group more likely to show up for in-person learning than peers of color.

A winter surge in Chicago’s COVID-19 cases, deep-seated mistrust of the district in some communities, and a bitter standoff with the district’s teachers union, which relentlessly questioned the district’s safety plans, likely contributed to the drop off. Significantly, the district had made it clear to families that they could opt out of in-person learning at any time but would have to wait until April to opt in if they selected remote learning — likely leading some parents to choose the hybrid model to secure a spot just in case.

That lower-than-expected January turnout gave the Chicago Teachers Union added leverage as it fiercely pushed back against the district’s reopening plans. But after the two sides walked right up to the line of a second teacher strike in 15 months, they reached a reopening agreement that some experts have hailed as the one of the most detailed and comprehensive such pacts in the country.

In the latest data shared Wednesday, roughly 22% of Latino students, 30% of Black students and 55% of white students are slated to return to in-person instruction during March. Roughly 30% of students with special needs and those in temporary living situations are scheduled to do so as well. About two-thirds of the returning students qualify for subsidized school meals, a measure of poverty.

“We are confident that as we demonstrate our ability to offer a safe in-person learning option, more of our families will choose to come back to school,” McDade said.

District officials reported that student attendance was down almost 2% during the second quarter compared to the same period last year; the dip was steeper in the high school grades and for the district’s Black students, who saw a 4.5% decrease in attendance.

Overall, students saw 4% more As and 3% more Fs. But the increase in As was most pronounced for white and Asian students while the rise in Fs was most marked for their Black and Latino peers.

At Wednesday’s meeting, some parents addressed the board in support of a list of demands from a coalition of family and community advocacy groups to improve remote learning and beef up mental health and other supports during the pandemic. Some said district officials should be less preoccupied with performance metrics, arguing in favor of more flexibility and “pandemic passes” for struggling students.

“The focus on grades, testing and compliance during a pandemic feels ignorant of the more pressing needs of our communities,” said Mary Huges, district parent and leader of the parent group Raise Your Hand.

A slew of parents also argued in favor of promptly sharing a concrete plan to reopen high schools. They spoke of an academic and emotional toll that the isolation of the past year has taken on teens — and insisted parents need to know now what the district envisions for later this school year and next fall.

District officials said they feel a sense of urgency about offering a high school in-person option but also brought up the complexities of social distancing and maintaining student pods in schools where students see different teachers in each class period. They said they aim to start meeting with the Chicago Teachers Union and a facilitator later this week to tackle a high school plan. They said they hope the process will be more collaborative than the recent elementary reopening talks — a hope that Chicago Teachers Union President Jesse Sharkey echoed during public comment remarks to the school board.

In the meantime, the district is opening three new high school learning hubs — sites where students can learn remotely with supervision — that will serve about 170 students.

School board chair Miguel del Valle said he balks at the idea of the school year passing without freshmen adjusting to their high schools and seniors preparing to leave them setting foot in the buildings.

“We cannot remain strictly remote for all our high school students,” he said. “This is unacceptable.”