As Nariana Castillo readied her kindergartener and first-grader Monday for their first day on a Chicago Public Schools campus in more than 530 days, glimpses of normalcy and reminders of its stubborn elusiveness nestled together everywhere.

In new lunch boxes, bottles of chocolate milk sat next to tiny containers of hand sanitizer. In a shopping bag full of school supplies, notebooks were stashed next to disinfectant wipes.

Across the city, hundreds of thousands of families like Castillo’s made their way to Chicago’s public schools for the high-stakes return to full-time in-person learning. Many brought a tangle of conflicting emotions, often deftly concealed from youngsters swept up in the thrill of that comeback. Some carried bitter disappointment that the delta variant’s rise over the summer robbed families of a school reopening once meant to be a key milestone of vanquishing the coronavirus.

After a largely virtual school year in which attendance dipped and failing grades spiked — especially for students of color — there was also a blend of hope and uncertainty about the academic catchup and emotional healing students face in the months ahead.

And even as Mayor Lori Lightfoot touted $100 million in investments in a safe reopening, there were questions about whether the school district was ready. A last-minute flurry of bus driver resignations last week meant that more than 2,000 Chicago students would get cash instead of a school bus seat. Some educators worried that they couldn’t keep children the recommended three feet apart in crowded classrooms and hallways. Parents still had questions about what would happen should a campus report multiple cases.

“All of us are learning to do school again face-to-face,” said José Torres, the district’s interim CEO.

This summer, Chicago Public Schools required universal masking and vaccines for all its employees — mandates that the state has since embraced as well. But the district and its teachers union could not reach a written reopening agreement and traded sharp words on the school year’s eve.

Inside her McKinley Park home on Sunday night, Nariana Castillo set her alarm for 5:30 a.m., then stayed up until midnight, organizing supplies, making ham-and-cheese sandwiches, and texting fellow moms.

“We were messaging about how excited we are and how much anxiety we have at the same time,” she said.

Safety and sanity

Last weekend, Castillo had threaded a fine line between instilling caution in her two children — and letting their joy about the first day of school blossom. For both first-grader Mila and kindergartener Mateo, this would be the first time setting foot at Talcott Fine Arts and Museum Academy, on the city’s West Side.

Castillo let Mila pick out new unicorn sneakers flashing pink and blue lights with each step, and listened as she spoke about making new friends in the classroom. She also warned the children that they might have to spend much of the school day marooned at their desks.

She reminded them masks will be off at lunch, asking them to socialize with caution.

Still by Monday morning, Castillo could see Mila’s excitement taking off. The girl already raved about her teacher after meeting her on Google Meet the week before and fielding questions about Mila’s likes in Spanish. And, she said as she offered a parting treat of celery to the family’s “COVID bunny,” Stormy, “I get to have recess. I never had recess before.”

The shift to virtual learning had been jarring for Castillo’s children. The family had once held off on introducing computers or tablets, heeding advice about limiting screen time. Mila had attended Velma Thomas Early Childhood Center, a bilingual program that emphasizes hands-on activities, play, and time outdoors.

“My kids didn’t even know how to use a mouse,” Castillo said.

Mila adjusted to the new routines of remote learning relatively quickly. But Castillo, a stay-at-home mom, stayed by her preschooler Mateo’s side throughout the year. Castillo worried intensely that the pandemic was cutting off her children from social interactions crucial for their development. Still, in a part of the city hard hit by the coronavirus, the family chose to stick with all-virtual learning when the district offered a hybrid option in the spring. Says Castillo, “For us, it was safety over sanity.”

At a Monday press conference, city officials said they had worked for months to plan the mandatory reopening in the country’s third largest district — and reassure families such as Castillo’s that it was safe to return. For the first time, the district held its traditional back-to-school press conference at an alternative high school on the South Side, in acknowledgement of the uptick in students starting the year short on credits after some tuned out remote learning last year.

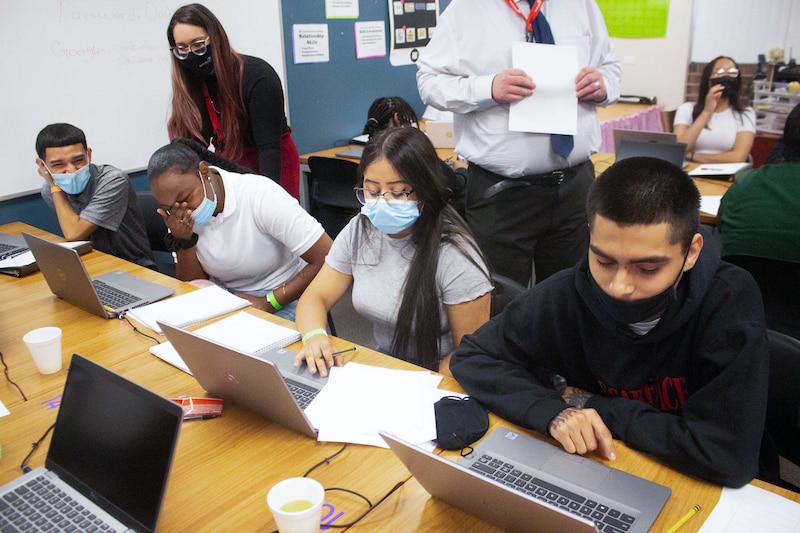

In one classroom at Ombudsman Chicago South in the Chicago Lawn neighborhood, seniors said they hoped the in-person push would help them finally complete a high school diploma after starts and stops brought on by personal crises, the pandemic, and the demands of off-campus jobs.

Margarita Becerra, 18, said she was nervous about returning to a classroom after a year-and-a-half, but the teachers had gone “all out” to make students feel comfortable. Even though everyone in the class was working at their own pace on an individual device, teachers roamed the room answering questions, helping Becerra feel optimistic she’d finish her degree midyear.

“Most people come here because they have a kid, or have to work,” she said of the half-day program. “We just want to get our work done.”

At the press conference, leaders emphasized the masking and employee vaccination mandates as pillars of the district’s strategy to rein in COVID transmission. Ultimately, Lightfoot said, “The proof has got to be in the pudding.”

Amid a national school bus driver shortage and the local driver resignations, the mayor said the district has a “solid plan” to deal with a shortage of about 500 drivers in Chicago. For now, families are receiving between $500 and $1,000 to arrange their own transportation. The district got word from its bus companies Friday that 70 additional drivers had quit over the vaccination mandate — an 11th-hour curveball that had parents such as Castillo bracing for another school year steeped in uncertainty.

“Is COVID gone?”

For weeks, Castillo had closely followed news about COVID case counts swelled by the delta variant and school outbreaks in other parts of the country. A few weeks before the school year’s start, she attended an information session with Talcott’s principal, Olimpia Bahena, who has won Castillo over with her regular emails to parents and her air of no-nonsense competence. Still, Castillo was unsettled to learn that district officials had not ironed out some safety protocols yet.

The district has since shared more details: Students who need to quarantine for 14 days because they get COVID or have close contact with someone who does will tune in to classroom instruction remotely for part of the school day. The district will offer voluntary COVID tests to all students and families weekly. But to Castillo, “grey areas” remain.

Later, Castillo met virtually with Mila’s first-grade teacher. At 28 students, hers would be one of the largest first-grade classes in recent years, putting into question the three feet of distance the district aims to maintain when possible. Lunch would be in the cafeteria, with another first-grade and two second-grade classes. Castillo was angered to see disinfectant wipes and hand sanitizer on the list of school supplies parents were asked to bring to school. The district received billions in pandemic recovery funds from the federal government, some of them meant to pay for protective equipment and supplies to reopen schools safely.

The week before classes started, at the dinner table, Mila asked abruptly, “Is COVID gone?”

Castillo took a breath. Not much is more important to her than shielding her children from the stresses of the pandemic.

“No,” she acknowledged.

“Then why are you sending me to school?”

Time to be back

On Chicago’s South Side, Dexter Legging feels no hesitation as his two sons head back to school this fall. His boys need to be in the classroom.

A volunteer with the parent advocacy group Community Organizing and Family issues, Legging has been a vocal proponent of reopening schools full time since last summer. He feels the district has taken important steps to reduce the risk of COVID transmission, but he also points out that any discussion of keeping kids healthy must feature mental health front and center. By cutting off his children from facetime with peers and caring adults and from after-school activities such as his junior’s football team, school closures have taken a heavy toll, he says.

Then, there’s academics. With his older son heading into his junior year at Al Raby High School, Legging has already created a spreadsheet to manage and track college applications. He is grateful teachers at the school have pushed and supported his son, who has special needs. But last year was a major setback, with his son occasionally tuning out virtual classes for extended stretches. Returning to school two days a week in April helped. Still, Legging was taken aback to see Bs and Cs on the boy’s grade report.

“Those should have been Ds and Fs — all of them; I know my child,” he said. “He is going to be a junior, but is he ready to do junior-level work? That scares me.”

But for Castillo and parents in her social circle, embracing the start of the school year has been tougher.

She is involved with the nonprofit Brighton Park Neighborhood Council, where she has mentored fellow parents navigating the school system. In a recent parent survey the nonprofit conducted, more than half said they wanted a fully virtual option for fall. Another 22% said they, like Castillo, preferred a combination of online and in-person learning that would mean smaller groups of students in the classroom and more social distancing.

Some parents plan to sit out at least the first week of school, Castillo had heard. At one point, she thought about not sending her kids back. But the family had worked hard to research and apply to elementary schools, and they are excited about Talcott’s bilingual program and arts focus. Castillo could not bear the thought of losing their spots.

Besides, Castillo felt certain: Her kids couldn’t do another year of learning at home. She couldn’t do another year. A former preschool teaching assistant who more recently got her credentials to teach, she has started applying for jobs.

On the first day of school Monday, Castillo and her husband, Robert, paused to snap photos with their children across the street from Talcott. Then, they all put on their masks and plunged into the bustle of parents, students and educators on the sidewalk in front of the school. The commotion — complete with bubbles raining down from the building’s second story, Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance With Somebody” on a stereo, and the school’s tiger mascot — made the red social distancing dots on the pavement seem like an anachronism.

“Are you kidding me?” Robert whispered, taken aback by the gaggle.

But seemingly unperturbed, Mila found her teacher and lined up with fellow students waiting their turn to enter the building. “OK, mis amigos, siganme!” her teacher called out, and Mila disappeared into the entrance without a glance back.

Cassie Walker Burke contributed to this report.