Illinois education advocates are concerned that low wages, burnout, and the coronavirus pandemic are making it harder to fill after-school positions.

The Afterschool for Children and Teens Now (ACT Now) Coalition held a press conference Wednesday morning to bring attention to challenges facing after-school workers, at a time when districts have an influx of federal coronavirus relief money to help get students back on track after the pandemic disrupted education.

Teresa Dothard-Campbell, program director for Lights ON for Afterschool at East Moline School District 37, said that her workers often work second jobs for additional income.

“A lot of times we’ll find that our staff have to find supplemental income,” said Dothard-Campbell, “so many people that are working in our programs are coaches and leaders in other areas within our community.”

Dothard-Campbell said that she was able to increase wages for her workers due to federal emergency funding, but it will be challenging to keep wages up to retain talent when those dollars are gone.

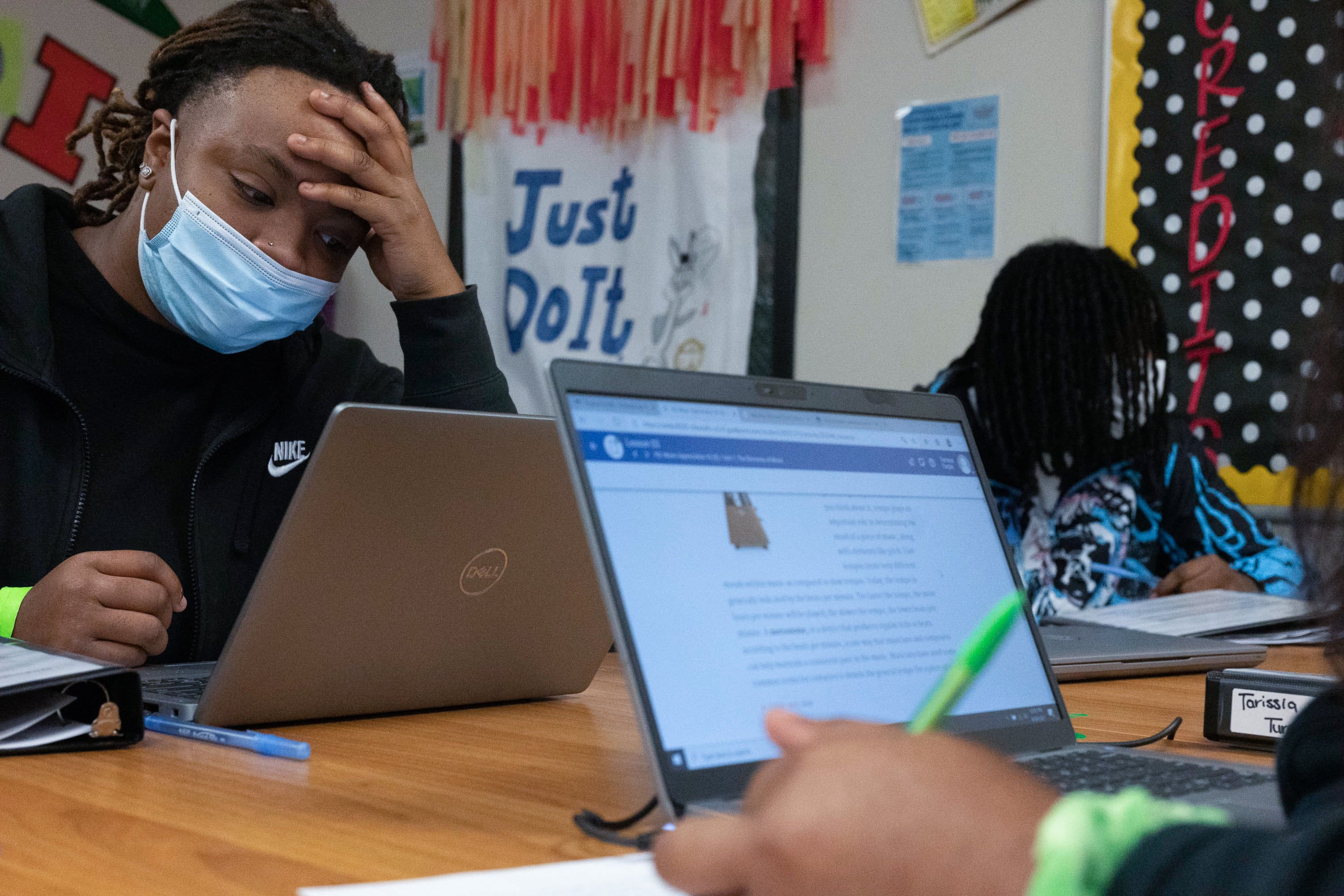

After-school providers already struggled to attract workers to jobs prior to the pandemic because of low wages and lack of job security. The pandemic has placed an extra burden on workers as they’ve had to juggle child care for their own children and limit exposure to COVID-19.

Some after-school providers have been able to increase funding for some workers due to federal emergency coronavirus relief funds, but most of those funds will expire in 2024. Illinois received $7 billion in COVID relief money.

There does not seem to be more help on the way as the Biden administration’s Build Back Better bill failed in Congress and the Inflation Reduction Act, which passed the Senate and is expected to be approved by the House, has no money for education or child care.

ACT Now also released results of a survey that it conducted between January and March of more than 120 program administrators, site coordinators, school administrators, and frontline workers.

More than 60% of respondents said they make a salary of less than $45,000 and often have to supplement their earnings with other income. A quarter of all respondents said they considered quitting in the past year.

The coalition’s survey reported that the majority of after-school workers are women who hold at least a bachelor’s degree. Advocates noted that low wages and burnout will make it harder to find skilled workers to fill positions and employers often do not have money for professional development to train their workers.

Maricela Bautista, director of youth services at Brighton Park Neighborhood Council, said at the press conference that her organization was struggling to find and retain staff prior to the coronavirus pandemic, but now health and safety are a top concern for employees and potential new hires.

“A lot of our funding goes directly to programming so there’s not a lot left for professional development,” said Bautista. “So we really need to make sure that the staff that we hire already has those skill sets when they’re coming in.”

The survey also looked into after-school workers’ concerns during the pandemic. A majority of after-school workers worry about child care for their own children, exposure to COVID, and their own mental health. Seventy percent of respondents reported being burned out due to the pandemic.

“Is it worth going into the school 12 hours a week, getting paid $16 an hour, and probably getting COVID because you’re working with students and adults?” Bautista said. “There’s a bigger risk and there’s more exposure.”

To help increase the pipeline of students going into the after-school workforce, Sen. Cristina Pacione-Zayas (D-Chicago), a former state board of education member, said at the press conference on Wednesday that the state will have to make significant investments over multiple years to see change.

“What I’m hearing is the need to be able to embed professional learning and development for individuals, provide tuition incentive and reimbursement, and mental and behavioral health interventions for the workers,” Pacione-Zayas said.

Samantha Smylie is the state education reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago, covering school districts across the state, legislation, special education, and the state board of education. Contact Samantha at ssmylie@chalkbeat.org.