Chicago students got more failing and incomplete grades during the pandemic, though that increase was much steeper at elementary schools than high schools, a new report out today finds.

But researchers with the University of Chicago’s Consortium on School Research say COVID-era grading data also offers some bright spots — and clues about how to steer recovery dollars to the schools that need them the most.

At the elementary level, twice as many Chicago Public Schools students got Fs or incompletes during the spring of 2021, compared with 2018 and 2019, according to a new consortium study of pandemic grading in the district.

But at the high school level, an uptick in failing grades was relatively minor, suggesting the majority of students remained engaged in learning despite the pandemic’s disruption. As previously reported, both elementary and high school students also earned more A’s, with many students who were previously getting B’s now receiving higher grades.

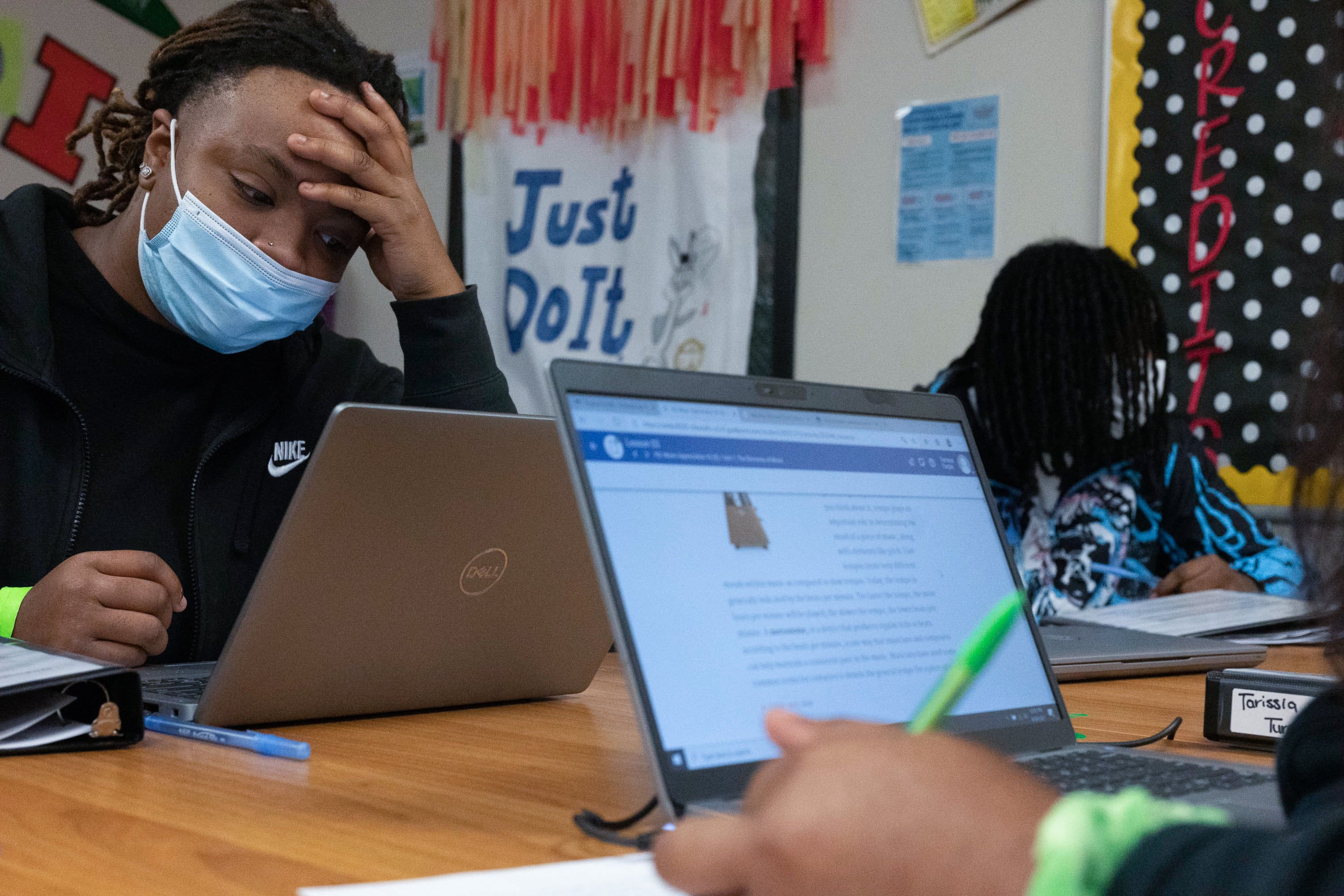

Racial, income, and gender disparities predating the pandemic continued during the outbreak. Elementary schools with the largest increases in failing grades and incompletes were more likely to serve predominantly low-income and Black students. But even among schools serving similar student populations, there were major differences in grading.

That variation merits closer study to see why some campuses were better able to weather the upheaval — and could guide efforts to target resources for academic recovery, said Elaine Allensworth, who leads the consortium and co-authored the study.

“We’ve seen the headlines about a ‘lost generation,’” she said. “The fact is that it was really hard for everybody, but most students were able to stay engaged.

“Let’s focus our efforts on the students who really had a hard time,” Allensworth added. “It’s a hard task, but it’s not an overwhelming task.”

Over the past year, emerging national test score data showing major academic damage from the pandemic has drawn much attention. But grades are also a revealing measure of how students have fared, Allensworth noted.

Chicago’s grading data raises some concerns, she said, but it’s not doom and gloom across the board. However, the study did not look at grades for first through third graders, cohorts that data suggests might have experienced the brunt of the pandemic’s learning fallout.

The consortium study zeroed in on grading among students in grades 4 through 12 during the spring of 2020, when all learning abruptly shifted online, and 2021, when Chicago school buildings reopened but most students continued to learn virtually. It compared grades to those from the 2017-18 and 2018-19 school years, the last two before COVID upended public education across the country.

For high school students, the portion of failing grades in 2021 increased only slightly — from 6% to 8% of all course grades — compared with the pre-pandemic years. A larger portion of high school students, particularly those who were earning B’s before COVID hit, got A’s.

The study did not explore the reasons behind these shifts, but some educators have reported giving students more grace amid the trauma and upheaval of the COVID outbreak.

At the elementary level, the picture is more troubling: During 2017 through 2019, about 11% of students in grades 4 to 8 failed a class. In spring of 2021, that portion had jumped to 21%. On some campuses, that increase was much more dramatic.

Allensworth said the differences between the elementary and high school level don’t come as a complete surprise: High school students are more mature, and their coursework is set up for more independent learning. In high schools, there’s also a stronger focus on ensuring teens stay on track for graduation, placing these campuses in a better position to flag struggling students earlier.

That said, the increase in high school students who struggled to stay on track with learning is real, and ongoing efforts to re-engage them are important, Allensworth said. If students disconnected from school in 2020 and stopped coming from school, for example, they would not be reflected in 2021 grading data.

The district needs to understand these differences better, said Allensworth, whose team is poised to explore that question through student surveys and virtual platform engagement data. The district’s school board is slated to vote Wednesday on a no-bid contract with the University of Chicago for up to about $286,000 to administer surveys of students’ classroom experiences.

“Everyone was trying to figure this out on the fly — dealing with the crisis as best as they could,” she said. “Some schools seem to have figured out better strategies.”

Mila Koumpilova is Chalkbeat Chicago’s senior reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Mila at mkoumpilova@chalkbeat.org.