Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

This year brought big shifts for education in Chicago and Illinois. As schools continued to return to normal and recover from the COVID pandemic’s impact on learning, the city elected a new mayor who appointed a new school board.

Schools grappled with a wave of migrants, who partly helped stave off continued enrollment declines, and the district entered a third straight year of transportation troubles.

As we approach the end of 2023 and look ahead to 2024, here are six of the biggest education stories we covered this past year:

New leadership to shape a new era

If the 2023 education beat had a theme, it might be leadership transitions. The state of Illinois got a new superintendent in Tony Sanders and Chicago got a new mayor and a new school board.

When Brandon Johnson, a former public school teacher, union organizer, and public school parent, made it into the runoff in February, he unexpectedly dashed incumbent Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s hopes for a second term. He would face Paul Vallas, a former CPS CEO who made a career as an education consultant and “fixer” turning around urban school districts.

Johnson’s victory over Vallas reflected, in part, ongoing shifts in local and national education policy. By July, he replaced six of seven school board members — a common act of new mayors — with more public school parents, community activists, and the leader of the parent group Raise Your Hand. The new board has already signaled some significant policy shifts, including moving away from a system of school choice and redoubling efforts to boost neighborhood schools.

What’s to come in 2024? Chicagoans will soon elect school board members, though state lawmakers are still working out the details of how that will happen. Before the legislature wrapped up its veto session, they did appear to agree on how the city would be divided into 20 districts after releasing their third draft of a district map.

COVID recovery money fuels interventionists, tutors

Federal COVID recovery money is dwindling and set to run out in 2024. But districts across the country have continued to spend millions on everything from tutoring to summer school to existing staff. In Chicago, more than $2 billion in Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funds have already been spent.

After months of questions and public records requests, Chalkbeat found a complicated picture of summer school spending in Chicago in February of this year. Many schools reported strong success in offering students robust programs, but tracking participation and attendance proved difficult. Data obtained six months after an initial request showed repeat sign ups or unusually high enrollments, raising questions about accuracy.

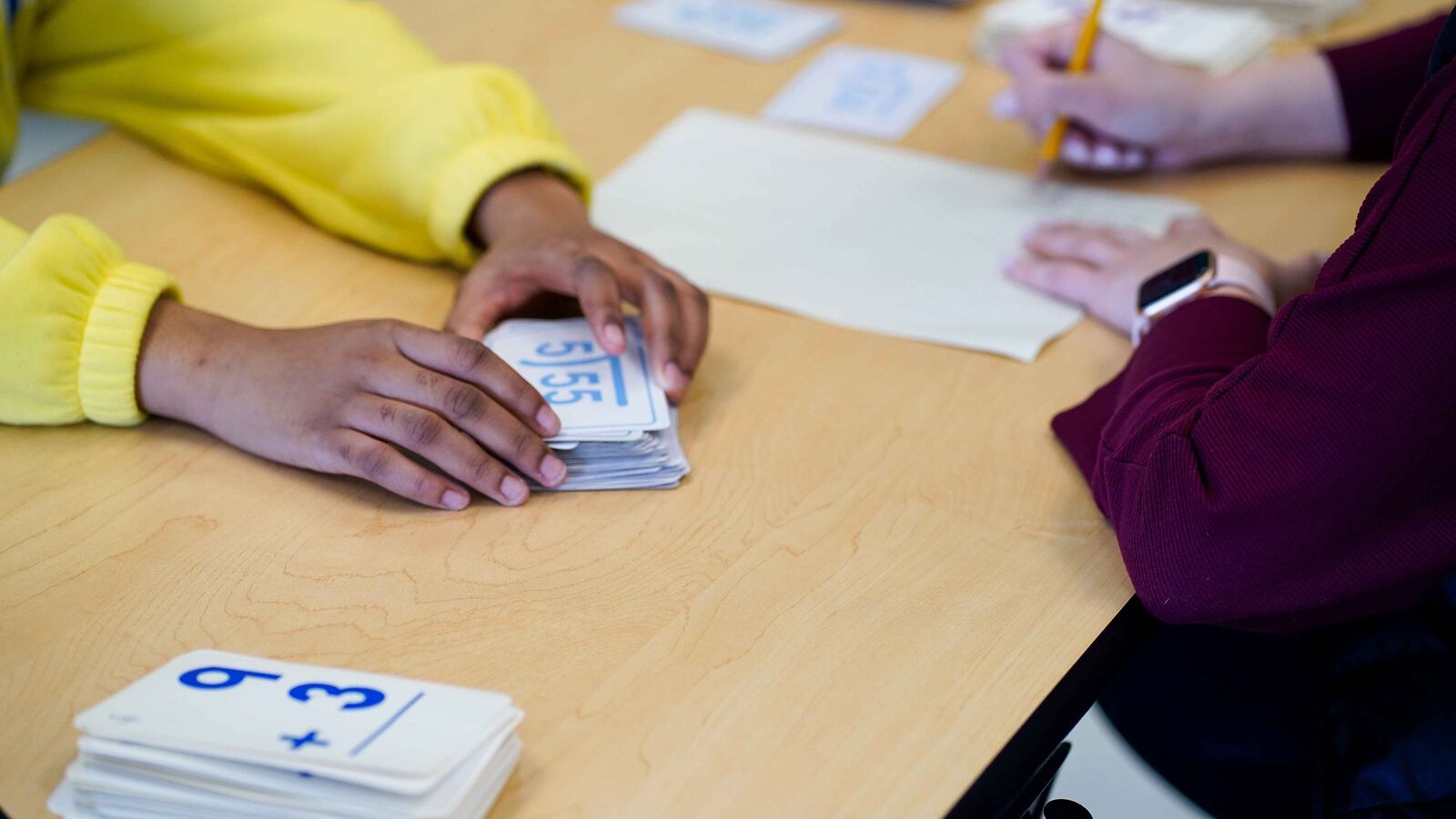

Chicago also continues to spend a large amount of its federal funds on existing staff, including a cadre of academic interventionists. These are mostly classroom teachers already on the district’s payroll who were tapped to help struggling students catch up. The district also spent $25 million to create a Tutor Corps to support students who may have gaps in their learning from when schools switched to virtual learning during the pandemic.

But the district is not only spending its money on staff. It also used some of the money to pay vendors to help develop a new $135 universal curriculum bank known as Skyline. In partnership with WBEZ, Chalkbeat took a closer look at how Skyline is being implemented and what teachers think of it.

Outside of Chicago, one south suburban school district is moving ahead with an uncommon technology plan to keep hybrid learning at the ready.

What’s to come in 2024? Chicago is planning to spend the final $300 million of the $2.8 billion it got in the 2024-25 school year and Illinois’ education budget could see some belt-tightening as districts set about spending roughly $1.9 billion of the $7 billion.

Schools see influx of migrant students

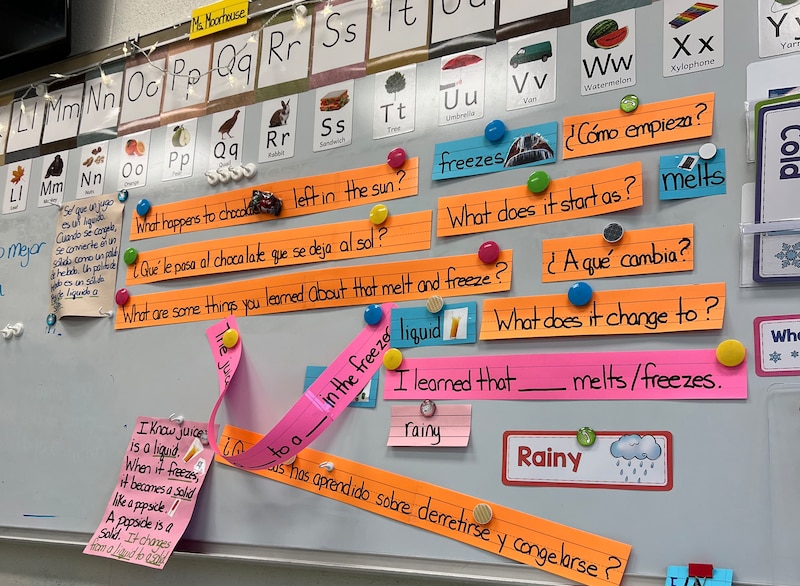

Chicago has seen an estimated 4,000 migrant students coming to the city from the southern border, most of them via bus from Texas. Among the many people stepping up to help families, especially children, adjust to a new country are teachers. During summer, we featured a few teachers volunteering at a south side police station to help refugee youth navigate a new language, a new culture, and in the fall, new schools. We also spent time at one school trying to help newcomer students navigate trauma.

Amid back-to-school season, it was not clear if schools would be ready to welcome waves of newcomers. A Chalkbeat analysis of staffing data obtained through records requests found the number of bilingual teachers had declined in recent years, but teachers with endorsements to teach in a bilingual program had grown.

What’s to come in 2024? Chicago continues to struggle to manage the influx of new arrivals, which has slowed in recent weeks. Plans to construct temporary tents in two locations have been put on ice. But the city instituted a 60-day limit on how long people can stay in temporary shelters just before Thanksgiving. However, migrant students do have a right to remain in the same school and receive transportation if they’re forced to move. (Leer en español.)

Special education sees shakeup

Chicago Public Schools has struggled to provide services to students with disabilities for several years and the COVID pandemic only exacerbated the issue.

In June, Chalkbeat obtained documents that found the district was violating state law on the use of restraint, timeout, and seclusion in school. Two days later, the top official overseeing the department that serves students with disabilities stepped down.

After that departure and after Johnson appointed a new school board, the district asked the public for input in hiring a new special education chief. In December, officials announced it had found a new special education leader from among its own ranks. Joshua Long, the longtime principal of a school for students with disabilities, was approved by the school board and will start his new role in January.

What’s to come in 2024? Long inherits a troubled department that remains under state watch for use of restraint, timeout, and seclusion in school. It also continues to face challenges providing students with disabilities with transportation, which they’re entitled to under federal law. Last year, hundreds of students with disabilities were on the bus for longer than 90 minutes each way, but that has declined significantly. Just over 100 were riding the bus longer than an hour, as of the end of November.

Transportation troubles continue

Amid state oversight, Chicago Public Schools announced in late July it would only provide bus transportation to homeless students and those with disabilities. Both groups are entitled to transportation under federal law.

Citing a bus driver shortage, district officials also offered families of students with disabilities and those in temporary housing a $500/month stipend to cover their own transportation, which nearly 4,000 families have taken as of late November. But those payments were initially delayed and the first checks weren’t mailed until late September.

By late September, district officials also confirmed that general education students attending schools outside their neighborhood, most of them selective or magnet options, would not get busing for the rest of the semester, leaving some parents grasping for help or switching schools.

What’s to come in 2024? CPS officials announced this week that the district would not provide busing to general education students for the rest of this school year. At a City Council meeting last month, officials outlined possible solutions for next school year, including having students picked up at a regional site rather than their home and working with schools to adjust bell schedules.

Preschool expansion goes statewide

Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker is promising to expand preschool and make child care more accessible in his second term. He said he hopes to make Illinois one of the best states to raise a family.

A longtime supporter of early childhood education, Pritzker’s push to boost the sector in his first term started off with a $100 million increase in 2019, but got sidelined by the COVID pandemic. Now, he’s making moves with a plan to increase early childhood by $250 million over the next four years and the creation of a standalone agency to bring together programs that are now housed across three separate departments. He also signed a bill requiring school districts to get up to speed by offering full-day kindergarten by 2027.

Chicago started rolling out universal preschool for all 4-year-olds in 2018, when then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel made it a re-election promise before bowing out of the 2019 mayoral election. Now, full-day preschool is a reality in every neighborhood, officials say, and enrollment figures from this fall show pre-K helped, in part, stabilize enrollment in CPS.

What’s to come in 2024? The governor typically gives a speech and releases a budget in early February. It’s likely he’ll continue increasing early education funding, but also could begin to detail the shape and scope of the new early childhood agency.

Becky Vevea is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Becky at bvevea@chalkbeat.org.