The Chicago Teachers Union filed a federal lawsuit Tuesday arguing that the government’s refusal to waive parts of its cornerstone disability rights law during the coronavirus pandemic has swamped special education teachers with paperwork.

The union, which named the city’s school board in the suit, said that the way Chicago Public Schools interpreted the law requires educators and school-based teams to essentially rewrite special education plans for as many as 70,000 students by the school year’s end. Union leaders said that’s a “physically impossible mandate” that diverts teachers from the already challenging task of serving students with special needs remotely.

The lawsuit criticizes how Betsy DeVos, the federal education secretary, has handled special education during the pandemic. Last month, DeVos decided not to recommend to Congress that school districts be given the option to waive key parts of special education law.

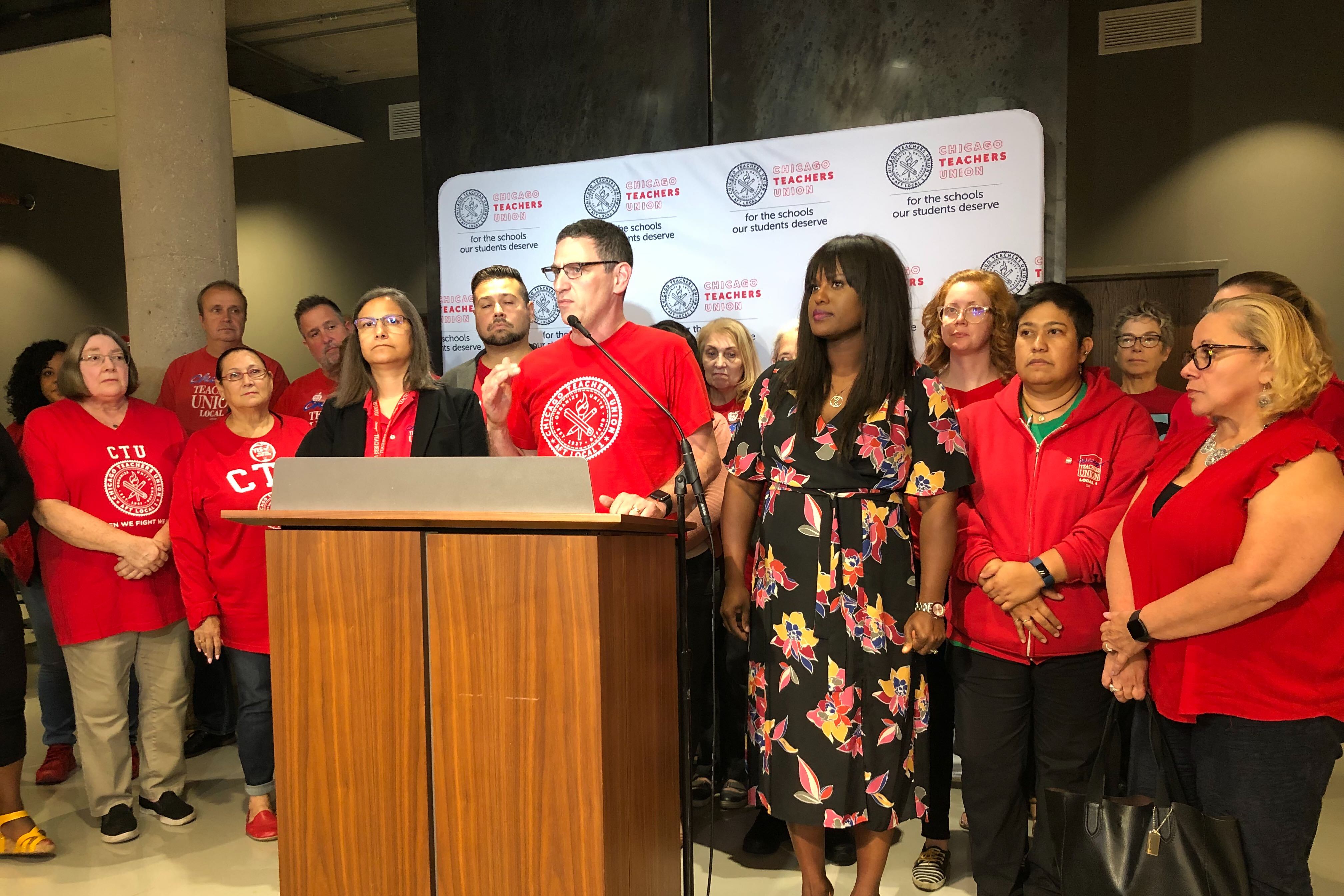

“We are looking for relief from onerous and unmeetable bureaucratic requirements,” said the union’s president, Jesse Sharkey. “What we need to be doing is having contact with our students.”

A spokeswoman for DeVos said the lawsuit is “nothing more than political posturing for a headline,” while a spokeswoman for Chicago Public Schools said the union did not properly characterize the situation.

The district said in a statement that its remote learning guidelines for special education do not require a wholesale rewriting of individualized education programs, or IEPs, the documents that spell out the services students with special needs are entitled to receive. Those guidelines just call on teachers to “make basic accommodations” to continue serving students under the unusual circumstances brought about by statewide school closures.

“Make no mistake: This lawsuit against the district is not about helping students,” said district spokeswoman Emily Bolton in the statement. “It’s about avoiding the necessary steps to ensure our most vulnerable students are supported during this unprecedented crisis.”

How to deliver special education services in a pandemic has become a flashpoint issue for educators and disability rights groups across the country. Advocates had feared the federal government might allow districts to ease protections for students with disabilities, but DeVos said in April that she would not, with a few exceptions. Still, some parents of children with disabilities have said they feel left behind as education has shifted online.

The teachers union suit this week states that the abrupt transition to remote learning amid the coronavirus outbreak has been especially taxing on students with special needs. It calls for the creation of a compensatory fund to pay for additional services, such as tutoring, therapeutic camps, and technology support.

Union leaders and educators said the district and federal government’s suggestions that teachers are using the lawsuit to shirk their responsibilities are deeply insulting at a time they said Chicago teachers and other professionals have gone out of their way to continue serving students. They said a lack of clear direction from the district and federal officials are making that job harder.

They said special education plans do need to be adjusted even if remote learning extends into the fall. But, they said, educators must get time and guidance from the district to accomplish what they described as a heavy lift.

Social worker Carolina Juarez-Hill said about the new remote learning plans, “We are trying to roll these out like an assembly line. We are trying to do it as quickly as possible because of the mandate.”

The union notes district guidelines require educators to review students’ special education programs and draft a plan to serve students remotely. The guidelines also say teachers have to hold a formal conference with parents or guardians to help draft the remote learning plans — a step that the union argues would create “anxiety and emotional distress” for parents during a challenging time.

The union says about 51,850 Chicago students have IEPs and another roughly 20,000 have other special plans, which cover non-instructional special accommodations such as those addressing food allergies.

After special education advocates filed a complaint in 2017 that Chicago systemically delayed or denied services to children with disabilities, the state school board placed the district under oversight. A monitor oversees the district’s special education efforts.

But the monitor has not yet issued a public accounting of how children with disabilities are faring in remote learning. Asked Wednesday for details on that by one of the state’s school board members, State Board of Education Superintendent Carmen Ayala said she’d provide an update at a future meeting.