When Giovanny Navarro went back to Finkl Academy, where he had worked as a paraprofessional, he wasn’t sure his students would remember him. But as he walked into the classroom last year, they came running, some of them crying and giving him hugs.

“We miss you! When are you coming back?” Navarro recalls them saying.

The answer? Today.

For many students, it was the start of another school year. But for Navarro, it was a day full of firsts: His first day back at Finkl and his first time officially teaching solo.

Last year, after working at Finkl for about four years, he took a break from the school — an intensive break — to learn from a mentor teacher at an elementary school in Englewood, while at the same time working on his master’s degree at National Louis University.

It’s all part of Chicago Public Schools’ Teacher Residency program. Launched in 2017, the program is tailored toward career-changers and district staff working in non-teaching positions, like Navarro. More than 150 teachers — the district’s largest group of residents since its launch — are in Navarro’s cohort. The vast majority are eligible to teach special education, early childhood education, or bilingual education, according to a CPS press release.

On Monday, Navarro said he was excited to be back and officially teaching at Finkl, a K-8 school where he’s spent years building relationships with children and their families. Finkl serves just over 200 students and is located between Pilsen and Little Village.

“It’s someone else’s kids, but they’re my students,” he said. “I always find ways to connect with them, to play with them, to teach them, to make their education memorable.”

He’s in his second year of his teacher residency. For the first year, residents are paired with a mentor teacher in a CPS school and paid roughly $40,000, according to the residency’s website. In the second year, they start teaching solo and earn a starting teacher salary of roughly $62,000. After completing the residency, teachers are expected to work for at least two more years in CPS.

The program aims to fill hard-to-staff positions, such as bilingual and special education teachers. Navarro is on his way to officially becoming both.

He still has some coursework to complete on his bilingual education endorsement, but Navarro grew up speaking Spanish. It’s a big part of why he chose to come back to Finkl — he said it’s where he feels like he can make the most impact. Nearly half of the students at Finkl come from non-English speaking homes and are learning English.

Navarro said he can relate. Around his sophomore year of high school, he migrated from Mexico to the U.S. and began learning English. Navarro said he hopes to help students like him to learn and believe in themselves. Over 5,000 new English learners joined the district over the course of last year.

“I have seen the struggle — how hard it is coming to a new country, where you don’t know people, you don’t know the language, the school looks totally different from other countries,” he said. “I want to be able to support students in not just education, but also in life.”

Navarro initially attended undergraduate school hoping to become a high school math teacher. But right after graduating, he started working in after-school programs at Finkl and said he fell in love with the work.

Since he had a secondary school teaching license, not an elementary school one, he couldn’t teach at Finkl right away. So he decided first to become a special education paraprofessional. But he said he saw an immediate need for special education teachers, especially teachers who could speak both English and Spanish.

After watching Navarro as a paraprofessional, Finkl Academy principal Nancy Quintana said she encouraged him to enroll in the residency program. Now, between his training in special education and his bilingual skills, she said, he could have been hired anywhere.

“There’s a national shortage, so he could have gone back to any school,” she said. “The mere fact that he came back to me is a true honor.”

Navarro said his training year required a lot of work — but ultimately felt rewarding. Both Navarro and his wife worked as teacher residents and returned to Finkl this year. In February, they had a baby boy. Juggling life, their own college work, and their jobs could get stressful, he said, but he’s grateful they could understand and support one another.

“We walked through this whole path together,” he said, “We both put a lot of effort into it. We were always doing what we had to and more.”

This school year, Navarro said he’s mainly focused on understanding his students, from their motivations to their challenges. For some children, he said, school cannot be their number one priority.

“Sometimes we need to be able to identify who needs that extra help, and what are the reasons students are acting some way,” he said. “Seeing things on paper and seeing who does good and who doesn’t is easy — really looking, talking to them and finding the ‘why’ is what is hard.”

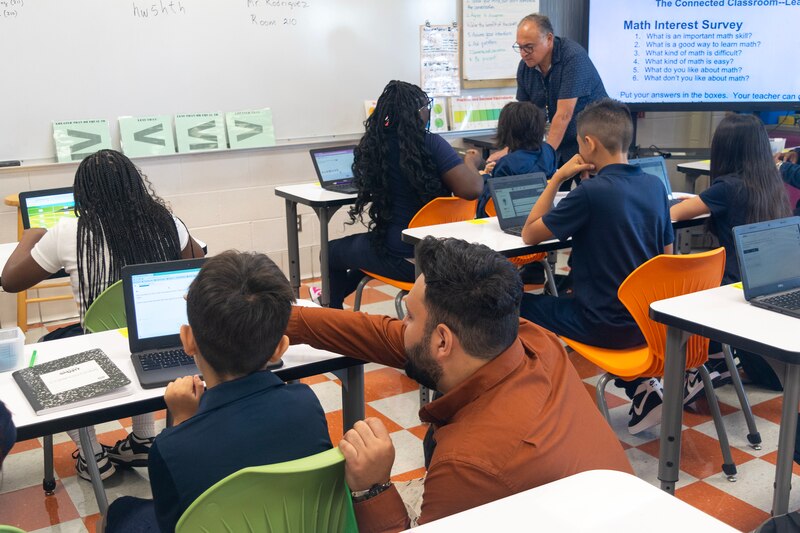

On Monday, he started laying some of that groundwork, spending most of the day getting to know his students and easing them back into learning.

He switched between classrooms, grades, and subjects. But no matter what or who or where he was teaching, he said he carried something with him: patience.

That’s his plan, for this first day and beyond.

Max Lubbers is a reporting intern for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Max at mlubbers@chalkbeat.org.