A week into the new school year, hundreds of Chicago students with disabilities were still waiting to receive bus service, officials said.

A total of 733 students with disabilities, who are legally entitled to transportation under federal law, were waiting for bus service as of Monday, according to a spokesperson for Chicago Public Schools. Additionally, 10 students living in temporary housing, who are also legally entitled to transportation, had yet to be assigned to routes.

Lacking half of the drivers it needs, the district decided this year to limit bus transportation to students with disabilities and those experiencing homelessness. These students can alternatively choose to receive stipends of up to $500 a month to cover transportation costs, which families of close to 3,270 children have done, the district said. The district is continuing to receive new requests for transportation, a spokesperson said.

For the families who haven’t accepted the stipends, the lack of bus service can be challenging, especially for students with disabilities who have varying needs. Working parents may not have the flexibility to drive their kids to school, and taking public transportation may also not be feasible.

The district said its policy is to pair students with routes within two weeks of their request, and it appears to be making progress. As of Thursday last week, 1,045 students with disabilities were waiting for a seat on a bus — about 300 more than the number at the start of this week. The district has also shrunk travel times for most students with disabilities, CPS CEO Pedro Martinez announced at last week’s board meeting.

However, that progress is happening as the district said it would not provide bus service this year to other students, including those attending selective enrollment and magnet schools. Those students have instead been offered Ventra cards, including another card for a companion, such as a parent.

Parents of some of those children, who are also struggling to accommodate their children’s commutes, sharply criticized the decision during a Chicago Board of Education meeting last week.

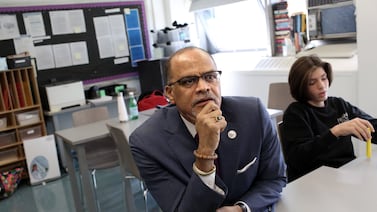

In an interview with Chalkbeat, Board President Jianan Shi said he understands “the challenges that this has on families.” But he believes the district is doing better, citing the improvement in commute times for students with disabilities, as well as the district’s efforts to address the driver shortage by planning to boost pay.

“CPS has the responsibility to serve our students with special needs and our students experiencing homelessness, and I believe we are doing that,” Shi said.

During last week’s meeting, chief operating officer Charles Mayfield said that even as the district has employed marginally more drivers, it has received more transportation requests. As of Aug. 19, the district employed 678 bus drivers, 22 more than it did at roughly the same time last year, a spokesperson said. The district has received just over 1,000 more requests for transportation as of this August compared to last year.

This is at least the third year that Chicago Public Schools has struggled to provide bus transportation for all students who are typically eligible. Last year around this time, roughly 3,000 students with disabilities were on routes that were longer than an hour, while more than 1,800 had not been routed, officials said.

The Illinois State Board of Education has taken notice of these issues. In 2021, state officials placed the district on a corrective action plan to ensure it was providing bus service to all students with disabilities whose Individualized Education Programs called for it. One year later, the state instituted a second corrective action plan to shorten commutes for students with disabilities.

Chicago bureau chief Becky Vevea contributed.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.