After six months in a downtown shelter, Daniela and her 11-year-old son, Luis, faced a dilemma: The city had given them until Feb. 1 to find another place to live, which would mean moving farther away from the school the fifth grader was attending.

The family, which migrated to Chicago from Venezuela, secured an apartment in South Shore with the help of Catholic Charities. Chalkbeat is using pseudonyms in this story out of privacy concerns for the interviewed families.

But their new apartment is more than 13 miles south of Luis’ school, Ogden International School of Chicago’s Jenner campus — which could mean an hour-plus commute by public transit for Luis and his mother, who had planned to look for a job.

Daniela’s predicament is one many parents could face as Chicago enforces a new rule requiring migrant families to leave shelters after 60 days. She is one of about 3,000 migrants who arrived between January and July 31 of last year and began receiving 60-day eviction notices in early December 2023, according to a press release from City Hall. If families haven’t secured permanent housing, they must get back in line for a spot at a city shelter.

But many migrant families in shelters might not know the rights their children have to district-provided transportation — or even that they can remain in the same school despite moving — if schools are not informing them, or there’s no one to help translate conversations between school staff and families.

Every school has a liaison for homeless students who is supposed to inform homeless families of their rights, a district spokesperson said. Those liaisons, along with principals and staff with the district’s Office of Cultural and Language Education, tell newcomer families how to apply for transportation services, the district said. Each school also posts a list of homeless students’ rights in English and Spanish near the main office, the district said.

Until Daniela spoke with a Chalkbeat reporter, she didn’t know that the federal McKinney Vento Homeless Assistance Act allows homeless students to stay in the same school even if they move, such as to another shelter, and requires school districts to provide transportation. It also allows students such as Luis, who have found permanent housing, to stay at the same school until the end of the school year. No one at the school had told her, she said.

In fact, federal law says that districts “shall presume” that keeping homeless students in their original school is in their best interest unless that’s against their parents’ or guardians’ wishes.

After publication of this story, CPS provided Chalkbeat additional details about how schools are informing families of their rights under the law. They said every newly arrived family gets an enrollment packet, both in English and Spanish, that includes information about the rights of homeless students, according to the district.

Staff at the district’s Office of Language and Cultural Education also help these families fill out an application for homeless students, which “provides families with the first opportunity to review the process and ask questions,” the district said. Schools have a 24/7 translation line that staff can use to communicate with families who don’t speak English. CPS said it fulfills its legal obligation to provide transportation to homeless students by providing them with CTA cards.

The goal of the federal law is to provide stability for homeless students. One 2015 study found that New York City students who transferred schools were more likely to be chronically absent, and of those students, those who were also homeless were more likely to repeat the same grade.

Daniela also didn’t know Chicago Public Schools allows parents of younger homeless students like Luis to apply for yellow bus service if they can’t accompany their child on the commute. Or that CPS policy requires schools to inform families who are homeless of their transportation rights and options.

“We’re not, as a district, transporting any newcomers,” said Kimberly Jones, CPS’s director of transportation, in late November during an interview with WGN. On Tuesday, a district spokesperson said the transportation department does not see students’ immigration status, but still called Jones’ statement accurate, in that she’s unable to identify any students on bus routes based on their immigration status.

But district officials have indicated they are tracking immigration status internally. At a City Council Education Committee meeting in late November, a district official testified that CPS had enrolled at least 4,000 migrant students.

This year the district is exclusively busing students with disabilities and homeless students due to a driver shortage and as it’s under state watch to shorten commutes for students with disabilities. District officials have said migrant students are largely homeless, meaning they’re living in shelter, doubled up with others, or in public places.

Of the roughly 8,700 students the district is currently busing, just 128 are homeless, the district said. Another nearly 4,000 students who would typically qualify for transportation this year are receiving stipends, with just 18 of them homeless.

The school did give Daniela and her son free CTA cards for the school commute to and from their shelter, a service it is providing as part of its legal obligation to provide homeless students with transportation. But, “they did not provide the option for yellow bus service,” she said.

Ogden-Jenner did not respond to Chalkbeat’s request for comment. The district also declined to comment specifically on Daniela’s experience.

Schools must inform families of their rights, advocates say

CPS policy also allows families of young children who are homeless to apply for “hardship” transportation, which provides yellow bus service for children who are in kindergarten through sixth grade. Caregivers must fill out paperwork to prove they have a conflict that does not allow them to assist their child in getting to school. Examples of “hardship” include work, job training, schooling of their own, a conflict with shelter rules, court orders, or another “good cause,” according to CPS’ website.

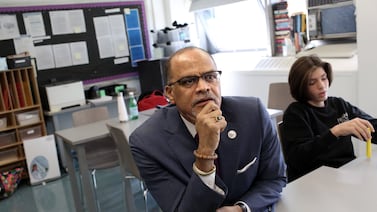

The 60-day shelter rule is “going to require families to move more often, and it makes it more challenging to get to the school of origin and stay stable in their school of origin,” said Patricia Nix-Hodes, director of the Law Project of the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless. “If they are eligible for hardship transportation, they should be getting it.”

“The onus isn’t on the family who is newly arrived to Chicago to figure out what services might be available for transportation,” Nix-Hodes said.

School liaisons for homeless students often have other duties in schools, which may make it difficult for them to keep homeless families adequately informed, Nix-Hodes said.

In addition to informing families of their rights, the liaisons should also help families figure out if they’re eligible for bus service and with filling out any required paperwork, Nix-Hodes said.

Other families are in the dark about transportation rights

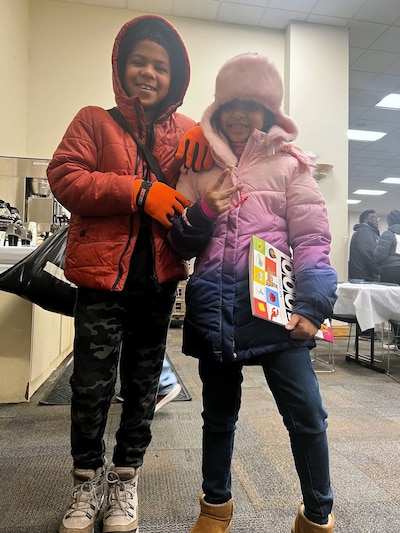

Edgar, a friend of Daniela’s who is also getting ready to move from shelter, also did not know he could apply for bus service so that his 8-year-old daughter could travel without him from their new home to her current school, Ogden Elementary.

Edgar is moving from the same shelter as Daniela to the same South Shore apartment building with his family. When he informed Ogden about their upcoming move, staff offered to find a school close to his new home — but they didn’t mention that he could apply for bus service to help get her to Ogden, he said.

After learning the information from a Chalkbeat reporter, he went back to Ogden to ask about bus service. The school confirmed that service was available but “these are things that take time to approve,” Edgar explained in Spanish.

Instead, with Ogden’s help, he plans to enroll his daughter at a school that’s a 12-minute walk from their new home. While his daughter is OK with leaving Ogden, she’s sad about leaving her English class, he said. Ogden did not return a request for comment, and CPS didn’t respond to questions about Edgar’s experience.

Schools shouldn’t encourage homeless families to “move schools when their living situation changes,” Nix-Hodes said.

The law allows homeless students to stay in their same school because school stability is good for children’s academic performance and social-emotional health, especially when they’re coming to the United States from another country, Nix-Hodes said.

Gwen McElhattan, a social worker with nonprofit Chicago Help Initiative, which provides meals, clothing, and other services to homeless families, has received questions from many migrant parents on how to enroll their child in school. The city has created a “welcome center” for migrants at Roberto Clemente High School, which is supposed to help families with school enrollment and other resources. But McElhattan said that many people don’t know it exists — and doesn’t sense that many designated people are informing families of how to navigate school enrollment.

“They don’t know about it because they’re migrants — they don’t always know everything that’s happening,” said McElhattan, adding that their primary concerns are food and shelter. “They’re just trying to survive. They have children – they’re just trying to keep going.”

Luis, Daniela’s son, said he likes his teachers at Ogden-Jenner and he’s made some friends. But he’s had a tough time understanding lessons because there’s often no one who can help translate, he said. Because of the language barrier, there are days that he doesn’t want to go to school, his mother said.

Still, Daniela would prefer to keep her son enrolled at Ogden-Jenner if she can get busing because she senses it’s a good school. By state standards, it is: The school earned the Illinois State Board of Education’s second-highest rating for academic performance.

Daniela has not yet talked with the school about what happens next or what her options are.

It’s difficult to communicate with staff, she said. “En la escuela allí no hablan español” — At the school, they don’t speak Spanish.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.