Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

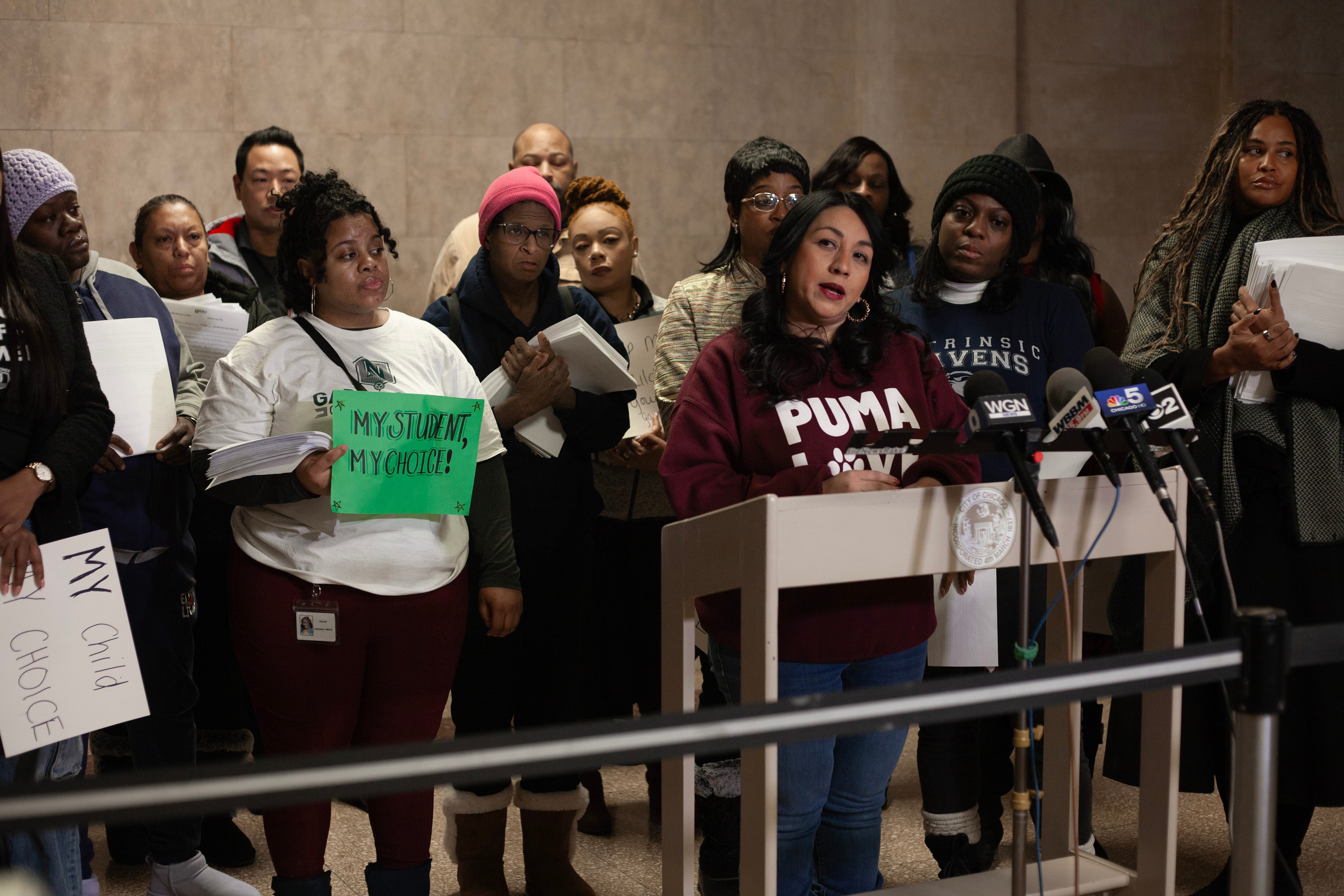

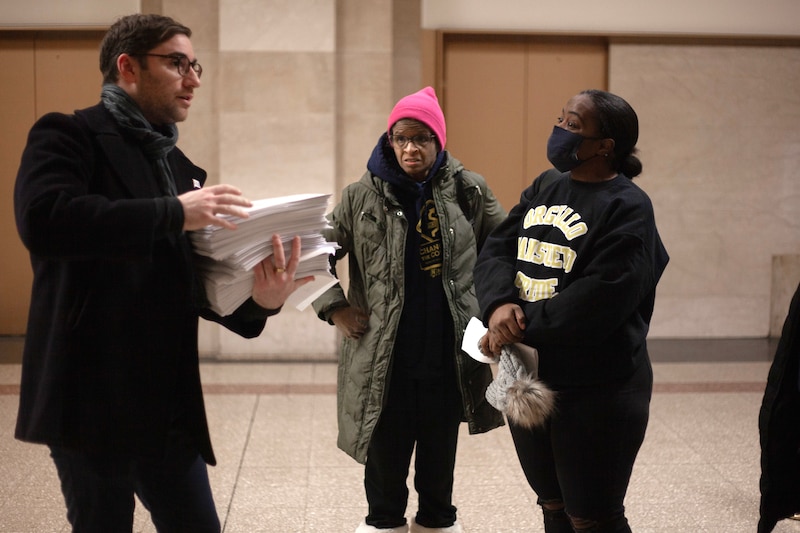

Charter school advocates delivered 2,000 letters to Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson’s office on Wednesday, urging the mayor to keep school choice alive, after his hand-picked school board signaled they may try to shift more resources toward neighborhood public schools.

Charter proponents are concerned about the future of their schools under a new mayor who campaigned on a pledge to boost neighborhood public schools — just as dozens of charters are up for renewal and a city moratorium on closing schools ends next year.

For roughly two decades, Chicago Public Schools has operated a system in which families can apply to myriad charter, magnet, test-in, or other district-run schools.

Having options for school was critical, said Myisha Shields, a parent of three former charter school students, during a news conference Wednesday at City Hall.

“My five babies, my Black babies — they’re gonna go where I choose for them to go, because that’s the choice that I was given,” she said. “I really don’t need Mayor Johnson’s help in choosing anything for my children.”

Shields, who lives near Marquette Park on Chicago’s South Side, said she has three children who attended charter schools and are now all pursuing nursing degrees.

She credits Noble Schools for the success of her eldest, who pushed through “severe learning disabilities” to get straight A’s at Alabama A&M University, where she’s a senior. Shields said her other two daughters are in their freshman and sophomore years at the University of Illinois Chicago. Shields said her kids wouldn’t have had the success they’ve enjoyed if they’d gone to traditional public schools.

“Her self esteem at one point was so low, but now it’s as big as City Hall,” she said of her eldest.

Noble Schools is one of 47 charters up for renewal during the 2023-24 school year. More than half of Chicago’s roughly 51,000 charter school students are enrolled at one of Noble’s 17 campuses across the city.

“We are calling for Mayor Brandon Johnson and his CPS board to demand a fair charter renewal term that protects school choice,” Shields said “If charters are not treated fairly, please believe: We will be at your door every day. This is not the last time you’ll see this face.”

In a statement, a spokesperson for the mayor said: “The Johnson administration believes in investing in neighborhood schools so that all of Chicago’s families have the choice to send their children to fully-funded, well-resourced, and celebrated schools in their community. As a former public school teacher, Mayor Johnson knows first-hand the harm that sustained disinvestment has on Chicago’s communities and youth. Furthermore, as the father of three CPS students, the Mayor is personally invested in ensuring the success of Chicago’s public school system.”

During the renewal process, district officials scrutinize charter schools’ academic performance, financial practices, and compliance with other standards. Chicago Board of Education members vote on the final renewal terms.

CPS spokeswoman Sylvia Barragan said in a statement that district leadership and the Chicago Board of Education “do not make charter renewal or revocation decisions lightly.”

The board voted last month on a resolution to move away from school choice and ensure “fully-resourced neighborhood schools, prioritizing schools and communities most harmed by structural racism, past inequitable policies and disinvestment,” according to the resolution.

It was the first time the board formally stated it wants to move away from its embrace of selective admissions and enrollment policies, because it “reinforces, rather than disrupts, cycles of inequity,” according to the resolution.

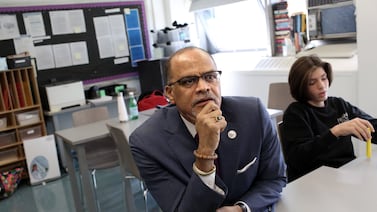

In response to worried charter and school choice advocates, Chicago Board of Education President Jianan Shi said during an Agenda Review Committee meeting on Wednesday that the resolution “is, again, about prioritizing neighborhood schools, creating pathways from K-12 and (helping) schools and neighborhoods farthest from opportunity, so that we are not sorting our children and favoring those with more means.”

He added that it’s “not directing us to close selective enrollment schools.”

Even before Johnson took office, former Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s administration started a trend of shorter charter renewal periods. Johnson, a former educator and organizer for the teachers union, historically opposed charter expansion and said during the mayoral election runoff campaign that charter school expansion “forces competition for resources and ultimately harms all schools.” But he also has said he does not oppose charter schools.

This story was updated after publication to include a comment from the Chicago mayor’s office.