This article is co-published with Crain’s Chicago Business.

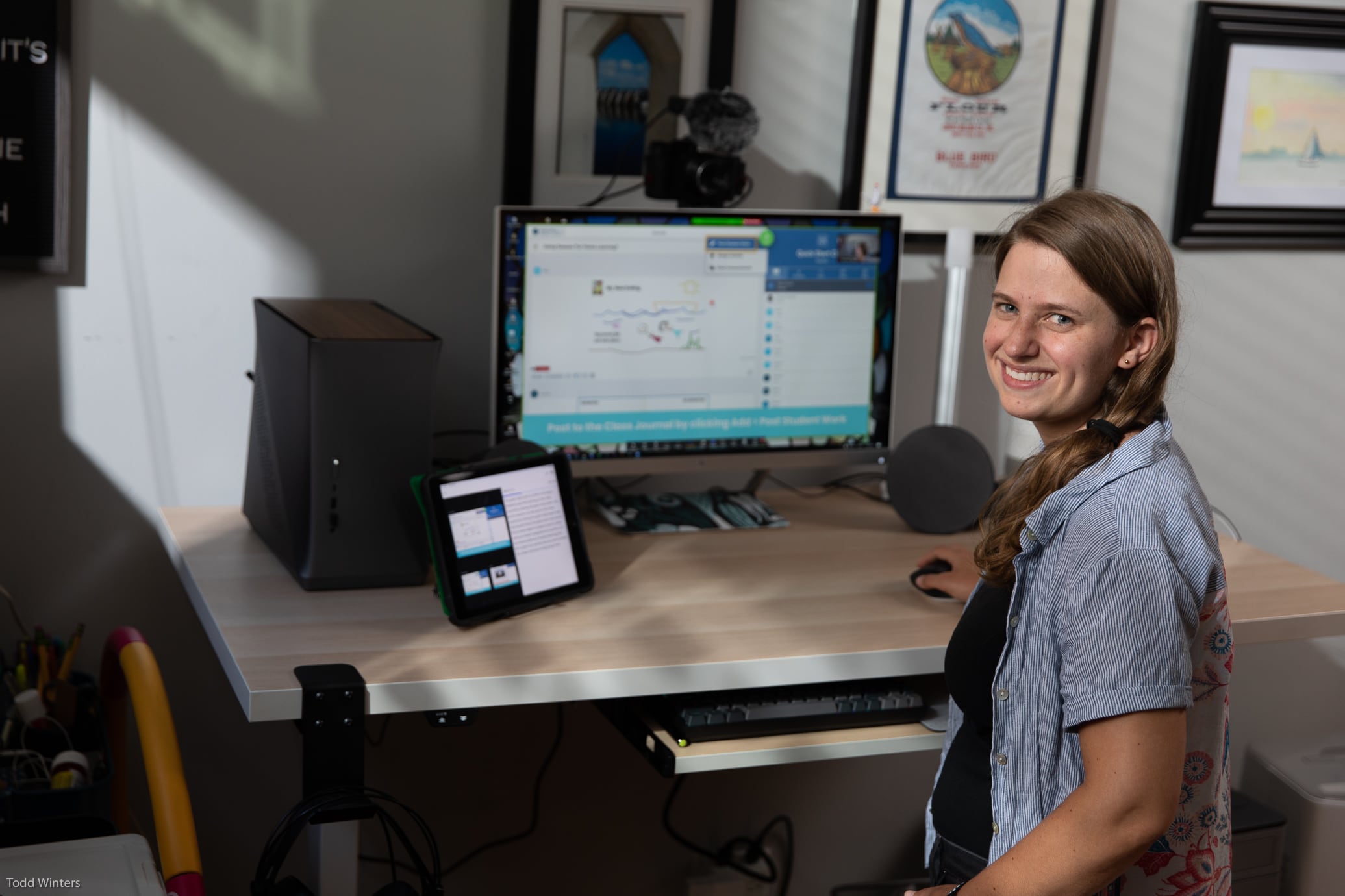

Claudia Martinez, a preschool teacher in Chicago’s Little Village, spent the summer combing through teacher Facebook groups for training videos on digital teaching.

Her school, Emiliano Zapata Academy, is nearing the new academic year, and her students’ needs are at stake, but her district has failed to lead, she says. She and other educators say Chicago Public Schools has been slow to roll out the professional development training they need.

Illinois districts, including Chicago, promised improved instruction for the fall. Overwhelmingly, administrators said remote learning would not be a continuation of the spring, dubbing some plans “Enhanced E-learning” and “Remote Learning 2.0.” Even as the summer stretch gave districts months to prepare—while teachers unions and policymakers stressed the dire need for training adapted to the virtual shift—few are ready to offer comprehensive and effective training, a Chalkbeat Chicago survey of educators, conducted through Aug. 15, found.

Two out of five educators said they haven’t received any training. One out of four have paid out of pocket, underscoring the burden teachers feel to improve the fall learning experience. The poll reached 200 educators across 66 districts in the state.

Questions weigh on Martinez: How does she get students to log on without already established relationships? How will she check in with parents? Will students cry while on video, as is common for the youngest students at the start of the school year? She wishes for support or guidance as she navigates these challenges, many of which are shared by teachers across the district.

Illinois educators told Chalkbeat they also wished their districts offered training on race and equity issues, social-emotional support and special education assessments, as well as engaging students virtually, translating a regular curriculum to online and—for those leading in-person classes—monitoring social distancing.

By its count, CPS will have offered its 21,000 educators over 1,000 professional development sessions this summer. But some teachers say they were not made aware of any training or could not access it.

The training touched on technology and Google Suite, the standardized learning platform this fall. Several educators told Chalkbeat the sessions were bogged down by technology issues. Others say they were not a good use of time and didn’t address curriculum content and special education evaluations.

Face-to-face classroom teaching doesn’t neatly translate to virtual spaces, says Alesha Daughtrey, executive director of the Center of Teaching Quality in Carrboro, N.C. Educators need to adopt different teaching strategies. She calls technology training “the digital equivalent of giving somebody a key to their classroom.”

CPS leaders rolled out some videos on their six instructional priorities but did not go into how to implement them in the classroom.

School districts historically have failed to offer effective and impactful professional development, says Kate Walsh, president of the National Council on Teaching Quality in Washington, D.C. Districts tend to take a “one-size-fits-all” approach to teacher training, but different educators have different needs and skill sets, she says, and successful training programs come from peer-to-peer instruction.

The National Teachers Academy, a South Loop elementary school, is developing its own remote-learning training. A teacher familiar with Google Suite will lead a session on how to set up a class on the platform. A kindergarten teacher will focus on remote learning that engages younger students. Fourth-grade teacher Autumn Laidler, who helped develop the program, says she waited all spring to hear from the district and didn’t want to wait anymore.

At Irene C. Hernandez Middle School in Gage Park, social worker Carolina Juarez-Hill will work with the assistant principals to integrate social-emotional support into classroom curriculums. But discussions around school-level training came only after months of waiting for CPS guidance—and getting little response. “We’re ignoring the elephant in the room. There’s been some form of trauma,” she says. “We can’t wait for someone to tell us or let us know.”

At Haines Elementary School in Chinatown, the principal has held weekly meetings to assist teachers. But the principal at Lincoln Park High School, appointed in the spring after a leadership shake-up, has not.

Who takes on the burden of teacher training?

Districts must lead the way with training for educators, and that training needs to be offered as early as possible, says Mark Klaisner, president of the Illinois Association of Regional Superintendents of Schools. Regional superintendents have asked district leaders to focus training sessions on remote learning, social-emotional learning and curriculum assessment.

The Illinois Board of Education made similar recommendations in June and strongly suggested all districts use professional development days to train educators on instructional methods and materials, health and safety protocols, and the mental health needs of students.

But district leaders are also limited in what they can do during the summer months. Professional development days are typically scheduled just before the start of the school year, and this year is no different. Klaisner says school administrators are working to strike a balance between respecting teachers’ summer vacation and offering additional support.

Although districts should have already rolled out professional development, there isn’t a window to deliver it, Klaisner says. District leaders may wait to offer professional development after back-to-school plans are finished.

But as teachers face an uncertain fall reopening, many are looking beyond the district for training, even if it comes with a cost.

Scott Zwierzchowski, a CPS social studies teacher, will have squeezed in more than 100 hours of training by summer’s end, through a graduate course on effective classroom management and restorative practices.

As part of the course, Zwierzchowski built lesson plans he could use in his virtual classroom.

He appreciated the training the district offered but said it didn’t address how to navigate remote learning environments.

“In these press conferences, in these emails, they’re saying, ‘We’re teaching teachers how to do remote learning,” Zwierzchowski says. “And I haven’t seen that. And none of my colleagues have seen that.”

In exchange for the $2,500 graduate course, he will receive credentials and a pay hike. Other teachers are paying smaller amounts but may not receive credentials or a pay increase.

Unions have also offered professional development. The Illinois Federation of Teachers organized sessions that look at anti-racism training, trauma-informed practices and remote learning.

Teachers who seek outside training must decide where to go and who can best serve their needs. Unions and universities have emerged as top providers for educators who are willing to pay, while social media platforms, as well as Nearpod and Simple K-12, are popular cost-effective providers.

Elsewhere in the state, Harlem School District 122 plans to reopen school buildings, but teachers say they need more guidance on how to implement health and safety protocols.

The central Illinois district released a guidebook and announced professional development options on remote learning and social-emotional support on Aug. 17, says Michelle Erb, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction. Several professional development specialists assisted teachers in the spring with the abrupt transition to remote instruction.

The district will offer a hybrid of remote and in-person classes, which pressures teachers to devise ways to lead engaging remote classes while also teaching with social distancing measures.

A music teacher in the district says she can’t even begin to prepare for the school year without more guidance from the district.

The district has delayed the start of the school year until Sept. 8 to give staff time to prepare, but third-grade teacher Linda Miller still hasn’t received much counsel.

“I’ve been teaching for a long time,” Miller says. “I’ve seen kids in the classroom. It’s pretty hard to keep them apart.”

Oak Park Elementary School District 97 in the western suburbs has partnered with the Center for Teaching Quality on professional development. The center’s Daughtrey says the district prioritized educational equity and social-emotional learning when it developed training.

Hannah Tatro, a District 97 kindergarten teacher, learned from outside consultants how to structure remote learning and build community online. She also has led technology sessions.

Oak Park teachers can engage in optional training that includes both in-house and outsourced training. The district, whose schools will be remote for the first trimester, will host an additional week of mandatory professional development training. Classes are scheduled to start on Sept. 1.

Tatro says the training has been crucial as she gears up for the fall. Without it, she says the promise of a better remote environment cannot be delivered. “When I talk to people I know who teach at other places, they’re not getting what we’re getting.”

For Sheila Lent, who has taught at CPS for 24 years, the uncertainty racks her sometimes. “I have days where I don’t do any research because I’m paralyzed by anxiety.”