For the most recent updates on Chicago Public Schools, click here.

6:45 p.m. No classes on Thursday

Chicago Public Schools classes will be canceled Thursday for a second day in a row, Mayor Lori Lightfoot and CPS chief Pedro Martinez said Wednesday. The closures leave parents in a lurch amid continued negotiations between the district and the teachers union.

The district and the teachers union remain in a gridlock over reopening after union members voted to go remote starting Wednesday until Jan. 18, citing safety concerns in the face of the current COVID-19 surge.

During a press conference Wednesday night, Martinez said the district had no choice but to cancel Thursday classes. Martinez expressed frustrations over the walkout, calling Wednesday a “very sad day” for students who were turned away from in-person instruction.

Martinez acknowledged challenges across the district amid the latest surge but said district officials were nimble and responding to schools’ individual needs as needed. “The right approach is not a hammer to close districtwide,” Martinez said.

Despite ongoing negotiations, Martinez said officials met with principals and hoped to open schools to students at some schools as early as Friday.

“The goal is to have academic activities at schools on Friday” for schools with enough staff, Martinez said.

Union leaders have called on the district to require a negative COVID-19 test for each student before returning to the classroom, ramp up weekly testing, transition to an opt-out model, and set a citywide or school-level metric for closing school buildings.

Among the sticking points are a metric to shut down schools and the switch to opt-out testing, Lightfoot said. The school district could remain in-person and be surgical by closing a classroom or an entire school if necessary but would not commit to districtwide closures, she said.

The mayor also said the district wouldn’t agree to opt-out testing. Parents need to give the district affirmative consent to any procedures at schools, Lightfoot said.

“If a parent wants to get their child tested, we will get them tested,” Lightfoot said.

Allison Arwady, the city’s health commissioner, said the district, in partnership with the Department of Public Health, would be working to try to ramp up testing by using school nurses to help with testing students and with contact tracing efforts at schools.

The Illinois board of education said earlier in the school year that districts must provide learning to students who are in quarantine or those who are medically exempt from in-person learning. School districts can use their remote learning or e-learning plans.

According to guidance from the fall, a district’s e-learning plan does not have to be approved by the local school district’s regional superintendent to be used — even though they usually are.

Local school districts can use emergency school days, if advised by the local public health department. Emergency days have to be made up during the school year, which could possibly extend the year.

Amid the district and union impasse, Lightfoot said the city had filed an unfair labor practice against the union to bring teachers back, but said she preferred to come to an agreement at the bargaining table.

2:30 p.m. Parents call for more safety measures

On a Zoom call, about two dozen students and parents from community organizations Raise Your Hand and Brighton Park Neighborhood Council aired their frustrations with Chicago Public Schools’ COVID protocols up to this point. They said the teachers union’s vote to pressure the district for a remote learning switch underscores the need for more safety investments.

Jennifer Baez, the mother of two children, said that she learned her son’s class was flipped to quarantine after she’d already sent him to school in December. The principal had posted a message on Facebook, but not all parents use the platform.

Baez had to rush to get her son, who has special needs, since he had already left for the day when she learned the class would not be held in person. “Anger, anxiety, fear – all of these things took over at once,” said Baez, whose son tested positive for COVID on Day 2 of quarantine and was ill for several days.

Parents and students on the call said that Chicago Public Schools needed structured protocols for notifying parents of cases, flipping classrooms, and communicating key decisions with parents in multiple languages.

They also called for more school-based vaccination sites (Chicago runs four school-based vaccination hubs plus a mobile van), better personal protective equipment that is readily available to students, an expansion of rapid testing, and a remote option for families who are not comfortable sending their children to campus. — Cassie Walker Burke

1:30 p.m. Principals weigh in

Weighing in on Wednesday afternoon in a group representing Chicago’s school leaders. The group said a member survey showed rampant staff and student absences earlier this week.

On average, 16% of employees were absent Monday in 225 schools where principals or assistant principals took part in the survey, released Wednesday by the Chicago Principals and Administrators Association. At the 10 schools with the highest absentee rates, 42% of staff did not report to work on average, with one campus serving predominantly Black students grappling with a 81% staff absentee rate.

According to the survey, roughly a third of students on these 225 campuses did not attend school Monday — a rate the association believes is within 5 percentage points of the district average for that day. In eight schools, more than 60% of students were absent.

Troy LaRaviere, the association’s head and a longtime district critic, also said more than 70% of school leaders surveyed said they at least partially mistrust communication from the district. He said three-quarters of members surveyed agreed that the district should shift to virtual learning for a week or two in January, with campuses that feel prepared having the option to stay open for in-person learning.

“The schools are not safe — a majority of the schools or at least half of the schools are not safe,” he said in a virtual press conference.

9:15 a.m. Early morning robocalls and teacher lockouts

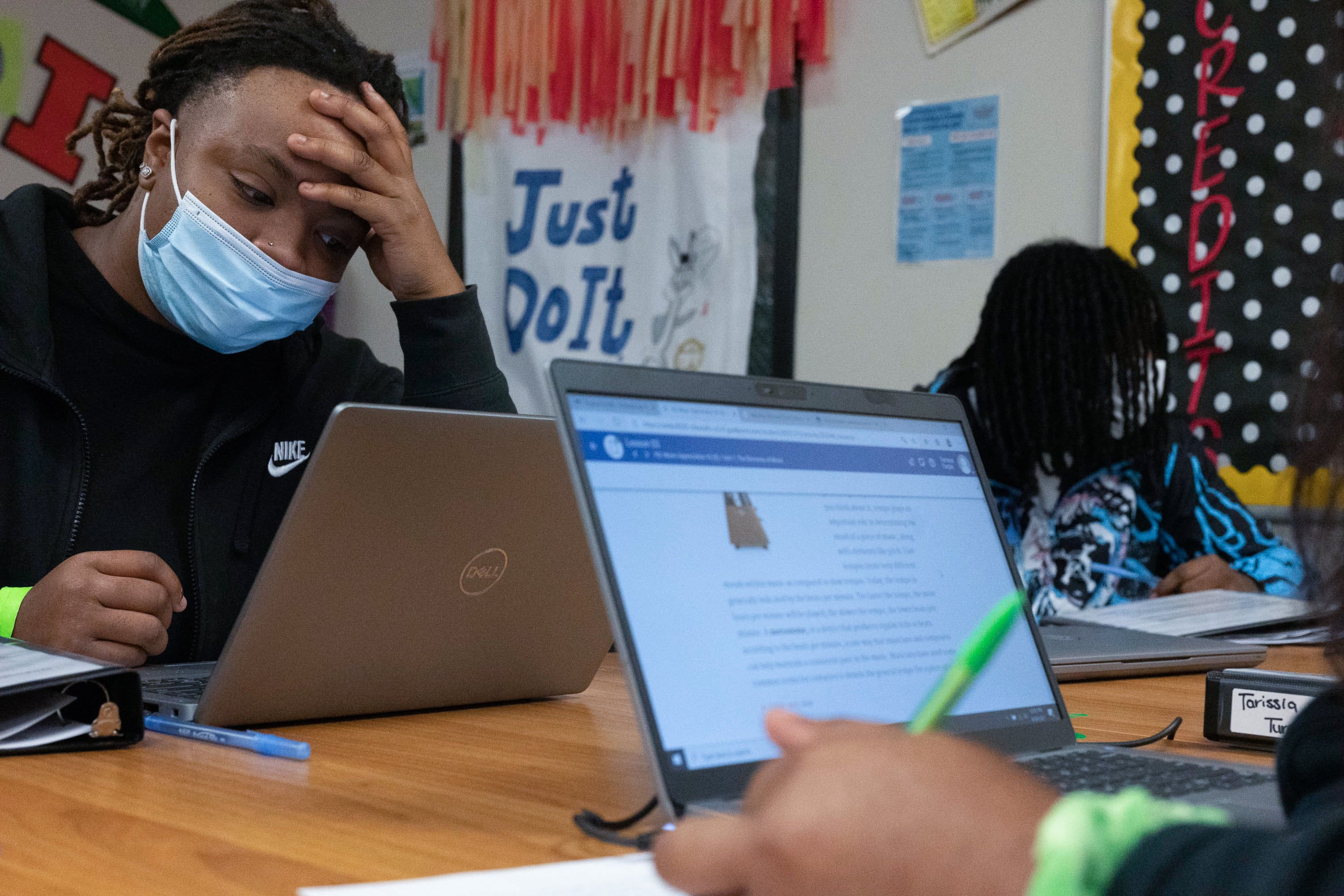

Chicago Public Schools families woke up Wednesday to canceled classes — the third consecutive school year when a standoff between the school district and its teachers union has brought learning to a halt, this time over COVID safety protocols.

The district blocked teachers late last night from their work emails and virtual classrooms after 73% of union members who took part in an evening vote backed ceasing in-person work amid the omicron surge. The district’s CEO, Pedro Martinez, warned teachers Tuesday evening that they would not be paid if they stop reporting to school buildings — what he and mayor Lori Lightfoot have called an “illegal work action.”

District and union leaders are slated to resume negotiations over a way out of the stalemate at 1:30 p.m. Wednesday. This morning, parents scrambled to make child care plans and waited anxiously for a promised communication later from Chicago Public Schools headquarters about whether the district would sanction remote learning while negotiations continue.

In an early morning press conference, union president Jesse Sharkey reiterated a demand that the district require each student to test negative for COVID-19 before returning to the classroom. Union officials said they also want a weekly student testing program that — unlike the current opt-in approach that has led to low participation numbers — requires families to proactively opt out if they don’t want their children tested. And the union wants a hard-and-fast citywide or school-level metric for closing school buildings, saying a district proposal that sets a high bar for educator and student cases and would only apply to January does not cut it.

If the district and union cannot reach an agreement, educators will not teach in person until the omicron surge ends, the union said Wednesday.

If the district and union cannot reach an agreement, educators will not teach in person until the omicron surge ends, the union said Wednesday. Union officials said teachers will return to buildings Jan. 18 — but only if the citywide COVID metrics no longer meet criteria for closure from a February 2021 agreement with the district, which set a positivity threshold of 10%. The current positivity rate is more than 23%.

“When the surge subsides — hopefully quickly — we’ll be back in the classroom doing in-person instruction,” Sharkey said.

Lightfoot, Martinez, and city health commissioner Allison Arwady sharply criticized the union’s move Tuesday evening, saying schools were just beginning to ease back into the routines of in-person learning and bounce back academically from a largely virtual last school year. They decried a late night, mid-week vote that thrust families into uncertainty and argued schools remain the safest place for children amid record high community spread. They vowed not to “sit idly by” while the union unilaterally moves to shutter buildings across the city, as Lightfoot put it.

Martinez promised to share a plan for the coming days with families by the end of the day Wednesday. School buildings will be open and serve breakfast and lunch until noon Wednesday; the district is providing some child care options at a number of “safe haven” sites and in park district field houses.

“I understand your frustration and deeply regret this interruption to your child’s learning,” Martinez wrote in a letter to parents sent Wednesday morning. “I also understand that you need certainty about what the coming days will look like for your students.”

Complicating calls for additional testing is a national shortage of COVID tests that has hampered access to kits and slowed down the release of lab results. Against that backdrop, a district push to distribute 100,000 test kits for families to self-test over the break ended in confusion when many tests yielded inconclusive results.

Union officials insisted the city can arrange for more tests.

“We’re committed to the negotiations process,” Sharkey said. “We’ll stay at the table.”

Almost 19,500 educators took part in the Wednesday vote, according to a union note to members, with about 14,300 voting in favor of staying remote. That means almost 60% of the union’s roughly 25,000 members voted for remote learning.

Union officials also decried staffing shortages in the district that they said have resulted in two or three classrooms combined in gyms or cafeterias this week. Staffing issues and substitute shortages have bedeviled districts across the country this fall.

The union’s press conference featured teachers and parents at Park Manor Elementary on the South Side, which flipped to virtual learning before the break after an uptick in staff and student cases sent most of its classrooms in quarantine. They implored the district to allow educators to teach virtually while the two sides negotiate an agreement — and echoed union leadership calls for stepped-up testing and a school closure metric.

“The line has to be drawn when we think about our physical and mental safety,” said Park Manor teacher Falin Johnson.