Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

More than 5,700 newly arrived immigrant students have enrolled in Chicago Public Schools since the beginning of the school year, district officials said Thursday.

Preliminary school enrollment data updated daily on the city data portal and analyzed by Chalkbeat shows overall enrollment increased by 4,500 students since the official count on the 20th day of school in September. After more than a decade of decline, CPS saw its enrollment stabilize this school year.

“The number is fluid and evolving,” CPS CEO Pedro Martinez said Thursday. “Our principals and teachers and school communities have been incredibly welcoming to the students and their families.”

His comments came during a virtual press conference about a new volunteer coordination effort launched by the City of Chicago aimed at supporting migrant families. It also comes after city officials once again delayed its plan to enforce a 60-day shelter stay limit on migrant families.

Publicly available data does not reveal how many CPS students are migrants or how many are living in city shelters. District officials said they do not collect information about the immigration status of students or their families “to support the City of Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance.”

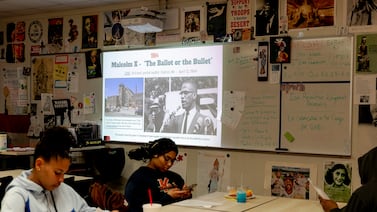

Preliminary enrollment data analyzed by Chalkbeat indicates nearly 7,000 more students have been identified as English language learners since the end of September, when the district officially counted enrollment. English language learners can include both newly arrived immigrants, as well as students already living in Chicago.

Last school year, English language learners made up about one-fifth of all students; a decade ago, these students made up roughly 16% of CPS.

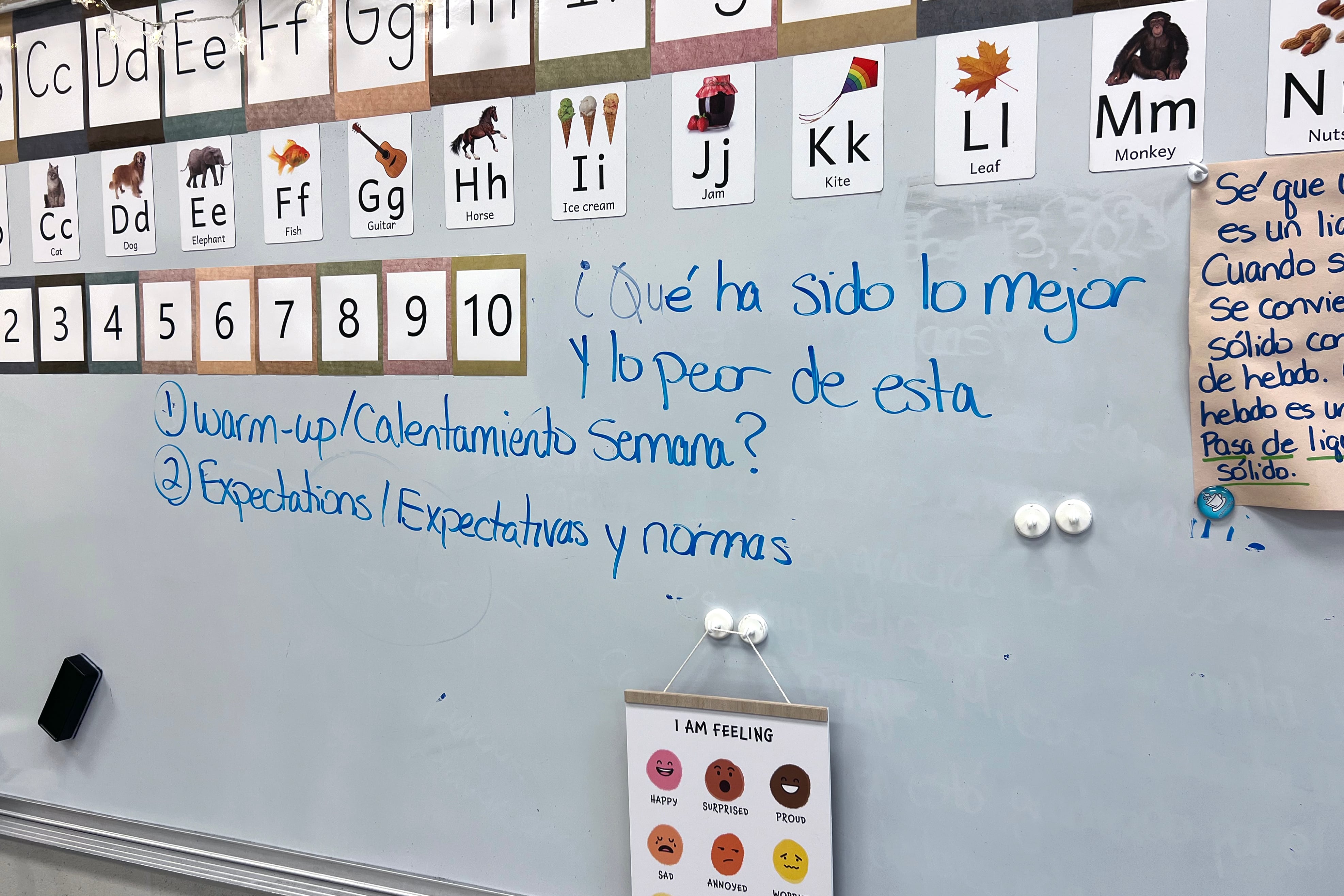

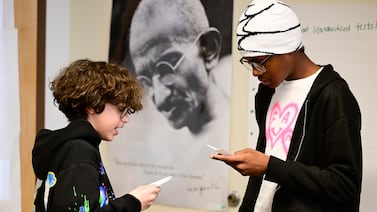

Last month, educators, union officials, and some local lawmakers raised concerns about schools without enough bilingual staff and other resources struggling to meet those students’ language and mental health needs.

District officials said Thursday that just under 6% of schools are lacking teachers with necessary ESL or bilingual credentials. Karime Asaf, the district’s chief of language and cultural education, said officials are prioritizing those roughly 30 schools — which officials did not identify — “for any kind of services or resources.”

Asaf said schools are working to get more teachers certified to teach English learners. District officials said they’ve allocated a total of $8 million to schools that saw increases in English learners since the 20th day of school.

Martinez said around 600 teachers are currently working toward getting bilingual or English as a Second Language endorsements.

Martinez said currently 7,200 teachers have these qualifications, up from about 5,100 teachers in 2018. However, bilingual staffing can vary by school, and often support staff, such as social workers, are not bilingual. CPS does provide a 24/7 language interpretation hotline that schools can call to get assistance communicating with families, but some parents have said they’ve struggled to communicate with schools or understand their school options when it’s time to move.

Students who are homeless — those in shelters, living doubled up somewhere, or living in a public place — have a right to remain at their school even if they move out of the school’s boundary and are entitled to transportation provided by the district, such as free CTA passes. By state law, if a school enrolls 20 or more students who speak a language other than English, the school must set up a bilingual education program with qualified staff. Asaf said this is “a multi-year process.”

“Generally, the challenge we have is when families just walk up to our buildings and we always tell our schools: Enroll the families. And then we have a process to work with those families to make sure we find the nearest program,” Martinez said.

The district also has bi-weekly meetings with staff at the city’s largest temporary shelters that are housing migrants, to “make sure that our families understand that there’s always a way to connect with the Chicago Public Schools … to make sure all their questions are answered,” Asaf said. She added that most school leaders attend these meetings.

Martinez said CPS is planning to hire newcomer adults who have received work authorization for “critical needs” at schools, including as custodians, as well as positions in transportation, nutrition, and classroom support.

Many of Chicago’s migrant families have been searching for work but need authorization to obtain jobs legally. Axios reported that about 1,000 newcomers have received work permits as of late January, four months after the federal government expanded eligibility to nearly half a million immigrants from Venezuela, where political and economic turmoil has pushed many residents to leave.

“We were proactive working with the city to say, since we know we have these families who are looking for jobs, we have many openings,” Martinez told reporters on Thursday. “We are now just trying to make it easier for our families to be able to apply for these different jobs.”

Becky Vevea is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Becky at bvevea@chalkbeat.org. Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.