Illinois public school students outperformed students who received tax credit scholarships on state standardized tests in 2022 and 2023, according to a new report submitted to the Illinois State Board of Education.

But researchers say the lack of demographic data for tax credit scholarship recipients limits the conclusions that researchers can make on the effectiveness of the program. While advocates who opposed the tax scholarship program say it raises questions about oversight into private schools who are receiving public dollars.

Illinois’ controversial tax credit scholarship, known as Invest in Kids, was created in 2017 amid a budget impasse between Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner and a majority Democrat general assembly. The program allowed people and corporations to donate money to organizations tasked with granting scholarships to low-income students to attend private schools. Donors would get a tax credit worth 75 cents for every dollar. Now the program is sunsetting after failing to get renewed during the veto session in the fall.

Supporters of Invest in Kids promised that the tax-credit scholarships would allow students from low-income families to get a better education than in public schools. However, a report commissioned by the state board and written by WestEd, a San Francisco-based nonpartisan research agency, found data to the contrary.

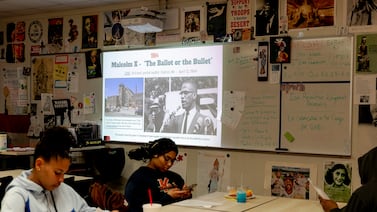

WestEd looked at test score data from the Illinois Assessment of Readiness, an exam that students from third to eighth grade take in the spring, scores on SATs, a college entrance exam for 11th graders, and surveyed how students, families, and teachers were doing at schools granted scholarship funding.

Among the report’s key findings:

- In 2022, 30% of students in public schools were proficient in reading on the IAR compared to 20.8% of those who went to private schools on a tax-credit scholarship. In 2023, the percentage was 35.4% in comparison to 22.5%.

- The gap in proficiency rates in math on the IAR was similar. In 2022, 25% of public school students were proficient in math while 17.8% of students who received the Invest in Kids scholarship were proficient; in 2023, the numbers were 27.1% versus 16.3%, respectively.

- On the SAT in 2023, public school students scored lower than students with a tax credit scholarship on English language arts; 31.6% of public school students were proficient in reading compared to 34.3% among scholarship recipients.

- On the math portion of the SAT, a higher percentage of public school students were proficient in the subject compared to scholarship recipients — 26.7% compared to 23.9%.

- Surveys of students and site visits also found that 95% of students said they feel safe at school and 81% said they like learning at school.

The report notes that data was missing for 34 schools that received Invest in Kids funding. In addition, WestEd said it could not analyze SAT scores for 2022 because some private schools included both scholarship recipients and students enrolled at the private school who did not receive a tax credit scholarship.

For the IAR test, WestEd could not find student-level demographic information and opted to compare scholarship recipient scores to the average statewide numbers. No data was available for students with disabilities and English language learners, the report said.

School voucher experts say while it appears that public school students are outperforming private school peers with tax-credit scholarships, it’s hard to make “apples-to-apples” comparisons without demographic data.

“It didn’t tell us anywhere near the amount of information about the schools serving these children as public schools have to report,” said Josh Cowen, an education policy professor at Michigan State University who has written similar reports. “Based on the little information we do have from the report, Illinois public schools are still looking pretty good relative to the private schools participating in Invest in Kids.”

Joe Waddington, a researcher at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana who has done research on Indiana’s voucher program, said the state board’s report didn’t say anything new about how voucher, tax credit scholarships, or education saving programs work.

“There’s nothing that sticks out here, particularly with test score results, that are any different from recent trends, which suggests kids’ achievement outcomes on especially state tests tend to be null or negative,” Waddington said.

Multiple studies reviewed by Chalkbeat on voucher programs in Indiana, Ohio, Louisiana, and Washington D.C. found that low-income students who attended private schools using a voucher did not see an improvement on test scores from attending private schools and proficiency rates in math were low.

Opponents finally see data after arguing for transparency

Opponents of the Invest in Kids scholarship have long raised concerns about the lack of transparency into the private schools serving tax-credit scholarship students. State law required the Illinois State Board of Education to provide annual reports on the academic progress of students attending private school using tax-credit scholarships.

The first annual report was supposed to be submitted in the 2019-20 school year. But a spokesperson for the state board said the coronavirus pandemic threw off those plans. Gov. J.B. Pritzker shuttered schools in 2020 and spring assessments such as the IAR and SAT were suspended for the year. While assessments resumed in 2021, student participation was low.

Cassie Creswell, director of Illinois Families for Public Schools, which advocated for ending the tax-credit scholarship program, said the findings in the report bring up the lack of oversight into schools that students with Invest In Kids scholarships attended. She said private schools should have provided more information.

“This does not happen with public school students. We have a lot of data besides the one pandemic year,” said Creswell. “That’s not the case for this program. It’s not okay to be diverting public funds from public schools that don’t have the same oversight, accountability, and transparency.”

Empower Illinois, which advocated for the creation of Invest In Kids and became one of the largest organizations to administer scholarships, released a statement on Tuesday saying the report failed to compare low-income students with Invest in Kids scholarships to low-income students in public schools.

“The Illinois State Board of Education makes testing data readily available to sort by income levels, but researchers instead compared low-income scholarship recipients to all Illinois public school students, rendering the results meaningless because they lack proper context,” the statement said.

A spokesperson for the Illinois State Board of Education said in a statement that”the absence of demographic data for the scholarship recipients and the lack of apples-to-apples comparisons between scholarship recipients and like-students in public schools” limits what can be gleaned from the report and noted that “ISBE did not have a role in creating or administering the program.”

The spokesperson said the report has been submitted to lawmakers.One of those lawmakers should be Pritzker, according to state law.

The governor said during the veto session that he would sign a bill to extend Invest in Kids if one made it to his desk. But that never happened.

“Advocates who supported the voucher program could not get the necessary votes to pass a bill during the veto session,” a spokesperson for the governor’s office said in response to a request for comment from Chalkbeat. “If their efforts are successful in the future the Governor will review the legislation, just like he does for all the bills that come to his desk.”

Cowen, Michigan State University professor, said the report is still important even months after the program has ended.

“It’s never too late to tell the truth,” said Cowen. “It’s never too late to shine a light on a program.”

Samantha Smylie is the state education reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago, covering school districts across the state, legislation, special education, and the state board of education. Contact Samantha at ssmylie@chalkbeat.org.