Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

The Illinois House has approved a Senate proposal that would allow Chicagoans to vote for 10 out of 21 school board members during the Nov. 5 election. The bill now heads to Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s officer for final approval.

Senate Bill 15, which passed 75-31 on Thursday, includes boundaries for the districts that school board members will represent, ethics guidelines, and term limits.

November marks the first time Chicago voters will be able to elect school board members. Voters will elect 10 board members while Mayor Brandon Johnson will appoint 11, effectively keeping control until the end of his first term. In 2026, all 21 seats will be up for election, with 20 members elected from districts and the board president voted on by the entire city.

The House vote Thursday comes just two weeks before March 26, when school board candidates can start to gather signatures to get on the Nov. 5 ballot. According to the bill, candidates will need to collect at least 1,000 signatures by June 24 to get on the ballot.

Rep. Ann Williams, a Democrat representing neighborhoods on Chicago’s north side, said Thursday afternoon that if this debate had taken place a year ago, she would have pushed for a fully elected school board. However, with November only a few months away, she feels the plan to elect 10 instead of all 21 is the best way to move forward.

“CPS is a $9 billion dollar agency which serves over 325,000 students,” said Williams. “It feels irresponsible to completely turn over the governance of Chicago Public Schools in a matter of months without adequate time to plan.”

While House members praised the work Williams and other lawmakers have done to establish an elected school board, others expressed concerns the shift in governance could impact the district’s finances.

Rep. Fred Crespo, a Democrat representing suburbs northwest of Chicago, said he is still worried about the financial impacts of Chicago’s elected board on the state and city.

A 2022 report required by state law detailed costs the Chicago Board of Education might take on as the board transitions to an elected board. For example, the report said, the City of Chicago could begin to charge the school district for things such as water and rent in non-district public facilities.

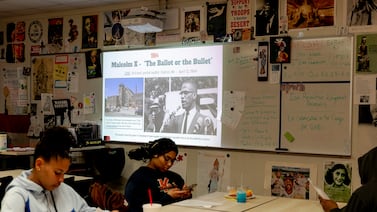

Chicago’s school board has been appointed by the mayor since 1995. For years, community organizations and the Chicago Teachers Union lobbied state lawmakers and rallied local support to get a fully elected school board. The effort gained momentum after school closures in majority Black and Latino neighborhoods on the city’s South and West Sides.

In 2021, the general assembly passed a compromise bill that created a hybrid board in 2024, which drew protests from local advocates.

Samantha Smylie is the state education reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago, covering school districts across the state, legislation, special education, and the state board of education. Contact Samantha at ssmylie@chalkbeat.org.